Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

Winter 1984. I’d been living in the Washington, DC area for about five months. To be specific, I was living in a shitty little apartment down the street from the Dischord House in Arlington, Virginia. It’s hard for me to describe how excited I was to finally be in the “big city.” Having grown up in central Ohio I’d always figured there was a wide old world out there, and I was meant to be in it. My original intent was to go to graduate school, but I was really in search of experience. I wanted it all. Politics, literature, art, music, food.

Related Posts

Ironically, it was the food that had drawn me to Adams Morgan that particular day. I’d read a blurb in the City Paper about a place called the African Room that specialized in a host of African regional cuisines. I’d never had African food, never been to Adams Morgan, and I figured I’d check it out. Back then before it got all yuppified, Adams Morgan and its adjacent counterpart Mt. Pleasant were the focal point of the Central American refugee community that had sprung up as a result of Reagan’s secret — and not-so-secret — wars. It was a rough but vibrant piece of real estate. I remember it was freezing. I don’t think I even owned a winter coat, so I was wandering up and down the streets looking for the restaurant and cursing my own stupidity. It was likely a gust of wind knifing through me that sent me scurrying for cover in the doorway of an abandoned building. When I looked up I was staring right at the flyer for a Sonic Youth show.

That event signaled my first experience of the infamous Wilson Center. In early ’84, it was notorious for random spasms of violence. Our nation’s capital had managed to spawn a serious cohort of little fascists who loved beating the ever-lovin’ shit out of each other at punk shows; order had not yet come to DC punk. So yeah, the air of danger that hung about the place appealed to me, but even more exciting was that I was finally going to see my heroes in the flesh. I’d played their self-titled 12” over and over and over again on my college radio show to the point where I actually got death threats from locals who were convinced that no one could actually like this music, so I must be giving them the finger.

So here’s the deal. I had a hell of a time growing up, and all of my struggles were internal. I’d like to say I didn’t like who I was. You know, embrace all that angst that’s so fashionable these days. But the fact is I didn’t really know who I was. I wasn’t sure if I liked myself or disliked myself. But I did know that I wasn’t particularly comfortable in my own skin. I never felt like I belonged. I could mask my insecurities really well because I had a sense of humor and I could make people laugh, but the bottom line was I had this burning desire to find my place in the world and, at the same time, I had no faith in any club that would have me as a member. I mean, damn, if people actually liked and accepted me, how cool could they really be? I was wandering around little more than the sum of all my contradictions.

Wilson Center has taken on iconic status in the history of DC punk — it’s hallowed ground. Bad Brains, all of the early Dischord bands, they played there; and, of course, anyone passing through town had to play there, too. There is a pretty interesting mythology that has sprung up around the DC scene, but I remember it was nearly impossible to find shows. The bars refused to book the bands and the spaces that were open to new music didn’t tend to last too long. In that regard, Wilson Center was special — a temporary autonomous zone in the midst of a remarkably hostile environment. And remember, I was 23 years old, and punk rock is a young man’s game. It was (and is) about house shows in basements and garages; it’s about high school. I was over-the-hill by those standards and dependent on random flyers (like the one I’d run across that freezing day in Adams Morgan) or the occasional notice in the DC City Paper, or word of mouth from the clerk at Joe’s Record Exchange. Regardless of how much I loved the music, the cultural geography of punk rock made it somewhat forbidding — or, at the very least, a real pain in the ass to get to.

The shows at Wilson Center were in the basement of the building, a long narrow room that looked — except for the ubiquitous black paint — like any number of multi-purpose rooms in church basements just about anywhere in the country. (Check out Cynthia Connolly’s wonderful Banned In DC if you’re curious about what the place looked like.) I got to the show late. I managed to wind my way toward the very back wall, climbing over the tangle of young kids who’d crammed into the room. That was my first impression of the place. I remember thinking, Holy shit, if something goes wrong in here people are going to die. Beyond cramped, no air circulating, humid and suffocating — in a word, “heaven.”

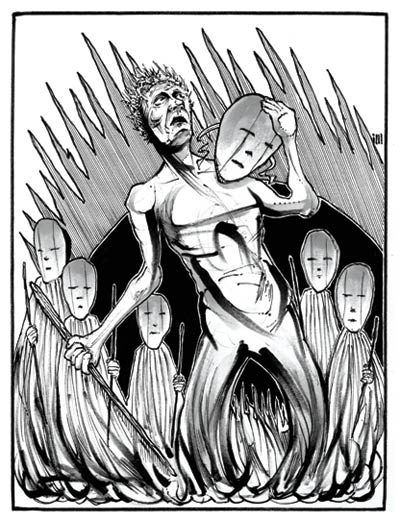

I won’t lie to you — I don’t remember a lot of the specifics of my first SY show. I’m not one of those people who remember set-lists. Plus, it was 24 years ago, so give me break! What I do remember is their epic volume. I remember the band lurching out of one of their noisy improvs into “The Burning Spear” and it was so loud I felt like my shoulders were pinned against the wall, like my ears were bleeding, like the rhythm section was pounding my diaphragm like a veteran boxer working the body. It hurt. It hurt so good.

But the best part of the experience was the connection I felt with all of those who’d crammed into that space with me. The wall of sound the band churned up that night swept all of us into the whirlwind of a collective experience. I remember looking to the young couple standing next to me. They were holding each other’s hands so tightly that I could see the whites of their knuckles. And they were smiling, big beatific smiles. They looked at me and we all knew we were experiencing something wonderful, ecstatic, transcendent. All of the people around us were looking at each other in the same way. We all knew that this was it. All the roads in all of our lives had led to this specific moment. We were meant to be there. All my worrying about fitting in, all those anxieties about whether I was living my life the way I was supposed to be, all the baggage of my young life drifted away. I was one with the sound. I’d finally found my place in the world. When it was over no one wanted to leave. I introduced myself to my new comrades. We ended up sitting out front for hours, smoking cigarettes, telling stories. I had found my tribe.

Related Posts

Spring 2008. The Bonaventure Arts and Media Fair (BAM) is held in the San Damiano Room on the St. Bonaventure University campus, a cavernous space that is a deconsecrated chapel. It has a wonderful gothic feel with Catholic icons leering from the raised marble landing where the altar used to be, and beautiful stained glass windows. Oddly, the space is rarely used anymore, and for the past three years I’ve helped a group of students turn that space into a celebration of art, film, poetry and spoken word, and, of course, music. For whatever reason there hasn’t been a place in the culture here for these people. They tend to create in isolation or for one another. There is little validation for those who’ve recognized that the do-it-yourself ethic can transform one’s life and give it real meaning. So once a year we throw a big party.

This year —every year — the bands are just incredible. This year they came from New Jersey and Connecticut. There was a wonderful folk singer from Fredonia, New York, and a remarkable duo from Buffalo. I marvel at what these kids can do with really rudimentary equipment — they can make technology dance.

You’ll be glad to know that I came through the wars of identity formation just fine. Maturity can be defined as the moment that you cease giving a squat about who you are and what you’re doing. It is that moment when you can just be. And let me tell you, not really giving a shit about all that existential nonsense works just fine. That, my friends, is liberation day. But I can see the same struggles that I weathered in my students. It’s in their reticence — in the effort it takes to not draw attention to one’s self. It’s like they’re walking through a minefield — one false move, and blam-o! Someone will know just how much it all hurts.

The last band of the evening was a duo out of Buffalo called A Hotel Nourishing. I’ve been writing about music since I was 15 years old, and, honestly, words fail me in describing their music. I think the rock duo (a la the White Stripes) has quickly become one of the most cloying of rock clichés. But these guys make a righteous noise! Guitars looped, slamming peripatetic drumming, they’re at once anarchy incarnate and mathematically precise; guitarist leaping, spinning, flailing, and yet elegant; drummer rolling and tumbling, jazz touch turned sledgehammer wielding fiend. It was totally sick! And loud as hell! Swirling, crunching squalls of white noise that echoed off the church walls — the space itself became a member of the band.

I caught myself smiling — a big beatific smile. And I looked around me and everyone was smiling. (Where are my Wilson Center friends now?) Some who’d been sitting were suddenly up out of their seats, urging the band on. Hell yes, I’d been down this road before, I knew where it was going and I had a new group of friends traveling with me. I wanted to yell at the top of my lungs, “This is it! All the roads in all of our lives have led to this specific moment. We are meant to be here! We are one with the sound!

Yes, I knew exactly where I was. I’d been here before. I was home. I had found my tribe.

—

Mark Huddle is the Editor of the National Affairs Desk of Verbicide. He teaches and writes from western New York. Check out his blog, “Trotsky’s Cranium,” at trotskyscranium.blogspot.com, or on Myspace at myspace.com/trotskyscranium. He can be contacted at mark@scissorpress.com.

Related Posts