Originally published in Verbicide issue #10

Originally published in Verbicide issue #10

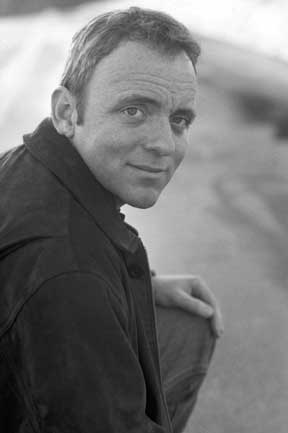

Dennis Lehane is widely gaining recognition as one of the country’s finest authors. After a series of five books about his detectives Kenzie and Gennaro, Lehane took a hiatus from the series for his 2001 effort Mystic River, which remains on the New York Times Bestseller’s list and was recently made into a Clint Eastwood film. His current novel, Shutter Island, was released this year to favorable reviews. The Dorchester native recently took some time to answer our questions about the movie, his books, and writing in general.

Related Posts

Now that the movie is out, what did you think about the finished product?

It’s excellent. It’s faithful to the book and it’s beautifully acted, so I’ve got no complaints.

What was the screenwriting experience like? Did you have any say on what would be left out of the movie?

I didn’t write the screenplay. Brian Helgeland did. Clint brought me into the process around the time of Brian’s third draft. I made a few suggestions, they incorporated the ones they agreed with, and that was it.

In Mystic River, the reader can sympathize with all of the main characters. Even when Jimmy kills Dave, you almost feel bad for both of them. Do you keep this ambiguity in mind when you write?

I don’t see much of the world in black and white terms. I’m much more of a believer in the grays. That morally upright, strong man of principle who walks through a lot of fiction, usually with a gun and a witty aside, bores the hell out of me. I don’t know that guy. Never met him or anyone like him. Same goes for the giggling “evil-doer” who rolls out of bed saying, “Time to do some bad,” and rubs his hands together with glee. Human beings are much more complex and interesting than that. So when I write, particularly as my books have progressed and I’ve hopefully matured a little bit, I keep asking what would this particular guy or woman do in this particular situation. And I try and let the character tell me his own truth.

I read that you wrote the first draft to A Drink Before the War in about three weeks. Did you write a lot of crime/mystery stories before this? I notice that you thank local law enforcement in your books. At what stage do you visit them with questions?

Yes, the first draft. And it was pretty shitty. What was published was probably the eighth draft. I’d never written a mystery before that point. I always wrote about violence, so I guess I made a natural transition at that moment into crime fiction. It’s a nice home; I dig the furniture and the people are fun. I don’t usually consult any experts on anything until after a draft is done. Mystic River was the exception because I needed to understand some things about turf differences between state and metro cops before I could really get going. Otherwise, I just throw it on the wall, see if it sticks, and then do some minor fact-checking at the end to see if I got it right.

You have a great ear for dialogue, especially for the area. When you’re writing a new character, do you often come up with their voice first, or do you know everything about them before you start with the dialogue?

Characters come out in so many different ways. There’s a lot of mental “method acting” involved when I build a character; I spend a lot of time trying to crawl into their heads and poke around and get a feel for all the stuff that’s below the tip of the iceberg and will never appear in the book. I’ve never known any writer who felt comfortable discussing the specifics of character creation. You just sort of do it and hope they start to feel real after a while.

The premise to Mystic River came from a “what if” of a real-life situation. Are your novels often loosely based on true stories?

There’s very little autobiography in my work. It suffocates me. If I liked facts I’d be a journalist. Mystic was inspired by that “what if,” yes, and there’s a minor scene in the book where Celeste recalls an injury she received as a kid that actually happened to me, but that’s about all the “me” there is in that book. My fourth book, Gone, Baby, Gone was triggered a bit by the Susan Smith case in South Carolina, but otherwise, I just make `em up.

What does someone drink to celebrate Clint Eastwood’s interest in his novel?

Beer, of course. I don’t really like anything else.

Tell us about your latest book, Shutter Island.

I didn’t want to follow up Mystic River with anything remotely like it and I’ve always wanted to write a gothic, so Shutter Island is my neo-gothic, I guess. It’s set in a mental institution on an island during the height of the Cold War and it’s a lot of me riffing on McCarthyism and paranoia and what someone once called the intrinsic fear humans have of The Other. It was a lot of fun to write, so hopefully that translates to the page.

What were some of the books that made you want to become a writer?

The Wanderers by Richard Price was the biggest influence. The Great Gatsby, Last Exit To Brooklyn, Billy Phelan’s Greatest Game were some others. I was inspired by a lot of Elmore Leonard’s Detroit novels, Pete Dexter’s stuff, the short stories of Raymond Carver and Andre Dubus. I’m a fanatic about Shakespeare’s tragedies and several of his histories, too. It’s a grab bag. I read a lot.

One last question. Some time ago — I think after Mystic River first came out — I read that you were doing something at the Kendall with the Dropkick Murphys, but for some reason I couldn’t go. I’m curious, did this really happen? And if so, how did it go and will it ever happen again?

That was part of an event called Earful which is run by my friends, Tim Huggins, Mike Deneen, and Jen Trynin. I’ve been involved in it since the get-go and one year we were trying to come up with the fall schedule and someone asked who I’d like to have perform with me because the previous year I’d gotten The Sheila Devine and that worked out well, so I said, “What the hell. Call the Dropkicks.” None of us expected them to say yes, but it turned out they were almost as impressed with me as I am with them. It was a great night. Legendary performance. Those guys just step out on a stage and kill.