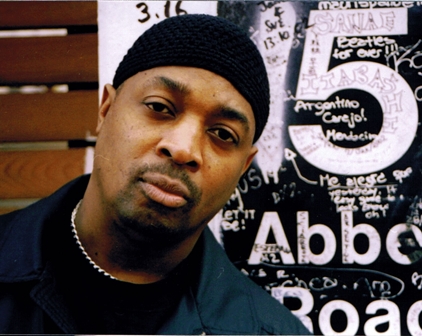

The world may not recognize it now, but I think it’s only a matter of time before Chuck D is recognized as hip-hop’s official chairperson. He holds his own both philosophically and musically, and every mechanic of modern rhyming goes back to his titanic influence, one way or another. The curved-lip melancholy of Pac and Biggie, the socioeconomic spouting of Kanye West, the Afro-centric bounce of Common — Public Enemy marked the beginning of all that. People like to say “Rapper’s Delight” is hip-hop’s genesis, but it was Chuck who made the genre matter.

The world may not recognize it now, but I think it’s only a matter of time before Chuck D is recognized as hip-hop’s official chairperson. He holds his own both philosophically and musically, and every mechanic of modern rhyming goes back to his titanic influence, one way or another. The curved-lip melancholy of Pac and Biggie, the socioeconomic spouting of Kanye West, the Afro-centric bounce of Common — Public Enemy marked the beginning of all that. People like to say “Rapper’s Delight” is hip-hop’s genesis, but it was Chuck who made the genre matter.

Verbicide recently caught up with Chuck D after his appearance at Sasquatch Festival, and we talked about his current projects, his radio show, and any nostalgia he might harbor for the ’80s and ’90s. The results were predictably thought-provoking.

Related Posts

What have you been up to lately?

Well, we launched hiphopgods.com, so we want you guys to sign up for hiphopgods.com and publicenemy.com — you know it’s the granddaddy of it all. It’s the longest running rap group hip-hop site, maybe other than the Beastie Boys’. And also we’re releasing an album box set this year of the last 10 years post-Def Jam called Bring the Noise: the hits, vids, and docs box set.

Are there any remasters on that, or is it original cuts?

It’s all remasters, the whole thing for the last 10 years, and also some remastered songs from our first CD.

And are you working on a new album right now?

Well, there is an album coming up that will come out in 2011, so it’s being worked together real slow.

So you’re taking your time on that one?

Yeah, of course.

The new record, which will be fan-funded via Sellaband, is going to feature many guests. Is there any particular reason for this? The other PE stuff isn’t exactly known for including guest performances, but this one sounds like it’s going to be different.

We [figured] it would make sense for [our fans] to invest in something different, so each song will have a collaboration.

And it’s got Tom Morello on it, right?

Yep, so far he’s committed. This is what makes this record different, you know.

Do you have a name for the new album?

Nope, no new name — really, I’m keeping my conversations low until next year. I know my publicist is putting it out there, but I’m talking very little about it. I’ve got to talk about this year before I get to that.

Fair enough — tell me about hiphopgods.com. What do you want to achieve with that?

I was inspired by what classic rock radio did in New York back in the ’70s — how they were able to separate the Bostons and the Thin Lizzies from the Beatles and other bands.

Related Posts

That’s great, because I suppose that there isn’t really a thing like that for hip-hop in this day and age.

It’s the supersite where classic rap lives on — if you go there and you check it out, it’s self-explanatory.

So is it sort of like an archival thing where you hold all that knowledge?

Yeah, we’ll finish up the final touches with hiphopgods radio.

What do you think PE’s message is in 2010? I’m expecting it must have evolved over the years.

Well, we’ve always been [for] peace, and if not peace, you know, fight the power. You’ve got to fight the powers that be that keep you from going forward — whether you’re fighting for the music or you’re fighting for your rights.

Right, so what would you say is your primary drive for keeping PE going at this point — do you enjoy the songwriting or do you think there still is a message that needs to be sent? You’ve outlived most other hip-hop groups — why do you think that is?

I enjoy the songwriting, I enjoy the performance art of it, I enjoy getting down with Flav, and I enjoy getting down with the fans — and I draw inspiration when I look and see a guy like Tom Petty getting down, or Mick Jagger. We’re the Rolling Stones of the rap game — Run-DMC was the Beatles, you know; I draw parallels from a lot of different cats doing these things so that’s the thing that drives me. I really get a kick out of it.

Nowadays you play a lot of festivals. Do you find those audiences to be pretty receptive?

Oh, of course, the audience is going to give you what you give. Years ago, the audience was harder to please. You had to work much harder because the standards were higher, but now the bar is so low that when you work really hard they are just blown away by it.

Yeah, we actually saw you play Street Scene 2009 here in San Diego which was loads of fun, so thank you for that. Do some negatives come with playing those types of shows, or would you prefer playing only festivals?

Well, last year and the year before were “festival years” that we didn’t tour. The United States has kind of morphed into a “festival nation,” or marketplace, but festivals work for us to get our message out — especially when you’re talking worldwide. PE was the first group — the first hip-hop group — that broke into the festival scene in Europe, [as well as] when festivals became more of a thing here in the United States.

For a while there it seemed to be that festivals were a little biased towards hip-hop — excluding hip-hop — but now there are events like Coachella, where you were on one of the main stages, and Jay-Z headlines Coachella as well.

They were a little biased towards the message and the energy that hip-hop was bringing. They wanted more of a dance party vibe, and we don’t have that — we kind of just come straight at you. But then the festivals became more open and more diverse as they evolved. In the United States, we were invited to play A Gathering Of The Tribes [a two-day festival precursor to Lollapalooza held in October of 1990] but we never [performed] because Flav was caught up in some benefit things in Philadelphia.

Do you ever have any nostalgia for the late ’80s and the early ’90s at the genesis of your career? Do you ever wish you could go back to the early days of Public Enemy with Terminator X and the golden age of Def Jam, or are you happy with the way things are now?

I’m happy with the way things are now, but I do miss Terminator X as well, just as a person. And, you know, a couple of the members have retired, so I miss getting down on stage with them.

Do you still keep in contact with them?

Well, not Terminator, for some reason; he’s a silent, quiet, guy and every time I hit him up, like, “Hey, we gotta get together,” then he goes back into his shell.

At this point in your career you’re pretty well-defined as to who you are as a musician — I mean, you have 12 records and they’re all pretty good; I don’t think you’ve ever had any bad periods.

Well, one thing we were always keen to do was not repeat ourselves. We take a totally unexpected route, and we’ve done that over and over again, throwing our career down a flight of stairs so many times — and that’s something that’s impossible for a lot of other artists.

But you’ve always kept the same basic themes of peace and revolution in your music — and I was wondering, if Public Enemy never happened, do you think that you would be comfortable with mainstream music and, specifically, mainstream hip-hop? Do you think that [revolutionary agenda] would’ve gotten across without Chuck D and Flavor Flav being in the fold?

I don’t know, because what we were doing wasn’t contrived. We were just being who we were, what we were, doing what we do — and understand that when we came out with our music, we were already eight to 10 years older than people in hip-hop at that particular time. But we drew from what we knew, and it totally wasn’t contrived. Everybody’s personality juxtaposed as it was. I tried to make everybody be a little bit more harmonious [stylistically], but, you know, that was part of the beauty of the tour, I guess.

Is there anything you would’ve approached differently with the message PE tried to send – musically or delivery-wise — or are you, for the most part, happy with what you’ve done as a group?

You’re never happy — you’re always gonna be like, “Damn, I could’ve done that shit better.” You know, the whole anti-Semitic [controversy with Professor Griff], I didn’t know how to handle that shit; nobody had precedent. It stemmed from an interview talking about Israel and Palestine — we were a rap group talking about a very hot issue, and we were in the middle of Switzerland talking about it. It happened to spread to the United States and it got taken to the next level with comments. But as far as me trying to figure out how to handle that…I mean, still to this day I wouldn’t have a clue. In hindsight, you can always say, “Oh, well, I could’ve said this,” but during that time — right then at that moment — nobody else even comes close. Even years later, good friends of mine — Sista Soulja, with her comments that were taken out of context about Clinton and the LA gang situation — they would come to me, like, “What’s up, how do I go about this?”

Rap music was brand new, and they never thought that it would say so much to so many people with so much impact. And it was so intriguing to the press to say, “Oh, we want to write about this,” but at the same time they were like, “Well, we gotta sell this magazine and this newspaper, so if you can, make it all sound like it’s scary and bad; that’s what we’re gonna do, and it’s not gonna be no skin off our shoulders.”

Surely there must be some resentment towards that attitude.

No, no, you can’t resent it. Media is not one synonymous thing, it’s the sum of many fragments floating in their own little spheres.

Public Enemy is now considered the de facto hip-hop group — like, you can’t write an article about hip-hop or claim to have an opinion about hip-hop without having some serious knowledge about Public Enemy. When you were in it before that happened — before the legacy was formed — did you ever think that what you were involved with would become so huge?

Well, I had three barometers, three bars to look at to be able to say, “Well, if we can get to that bar then we can see the next terrain,” and that was A) Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, B) Run-DMC, and C) the Beastie Boys. Those three acts right there made everything in the world possible. Internationally, it was the seeds that were left over from Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation that we were able to pick up and become the first golden age era group to try to get to the world aggressively and rigorously.

Related Posts

Would you say that that is a primary component of who you became? I’d imagine that you listened to a lot of Afrika Bambaataa before you started making music.

Well, I was a DJ, so I was listening to everybody and I played everybody, too. That’s one of the joys I have right now is doing a radio show called “And You Don’t Stop” on the Pacifica Network and in New York City; you can go to beyond.fm to check out the radio show. As a DJ in the ’80s, not only did we listen to everything, but we played everything, too.

Regarding contemporary hip-hop, do you trust the way that it’s evolving?

Well, I don’t know — how wide are you talking? Because, you know, when we do our radio show we have to do a search mission beyond what is commercially acceptable — and it’s easy to find because [of] MySpace. How many artists are on MySpace? How many artists are doing things independently in their own home? How many old artists — what we call “classic” artists — are still recording and performing today? That’s what we try to do with hiphopgods.com; we look to corral all this energy into one portal, and also reintroduce the latest “what haps” about these artists to the rest of the world. Like I said, if you go to hiphopgods.com you see a lot of energy and a lot of new efforts by classic artists.

As far as contemporary artists, cats are cutting, cats are cutting — but are cats being played? Are cats being presented in the past forms that used to do it? I mean, can you wait for BET or MTV or the radio stations that are only in business with the big companies? — [at least], what few of them are left. It seems like the big companies [that own] the radio stations and the record labels are kind of grabbing at each others shoulders, trying to hold on and stay afloat.

Do you think that there is a good way for underground hip-hop artists to get their music out there?

Underground artists need to find their own portal, and I think MySpace does it well. Hiphopgods.com — you gotta have some sort of classic relevance. You can be anybody to sign up and put your music up, but there are a certain [amount] of people who are accepted as the hip-hop so-called “gods” — and then everybody else is welcome to join in on that community. But on MySpace and Facebook, I believe there are communities that support everything else in hip-hop — we just take a small corner of that. We’re doing the same thing for women in hip-hop, and the only constraint is that you’ve got to be a woman — the name of that website is shemovement.com and the “she” stands for sistahs in hip-hop everywhere.

Are there any specific groups that you like right now? Mainstream or underground — what have you been playing lately on your radio station?

Wow, it’s a lot. The show “And You Don’t Stop” is inspired by Bryant Gumbel’s “Real Sports,” or “60 Minutes,” but it’s 180 minutes long, and it’s a show that works in four sections: the intro, the outro, a section that’s called “Songs That Mean Something,” and also “A Look Back Into This Week in Rap/Hip-hop History.” So I might talk about 1995, or I might talk about an artist or whatever in “This Week in Rap and Hip-hop History” — I’m going into the “classic zone” only.

On “Songs That Mean Something,” I might take a song from the past or the present and talk about it and play it; for the middle song, I take somebody that’s unknown who writes a song that means something; and then the third song that I pick is somebody usually from the hip-hop “gods” standpoint — a known classic artist who’s still cutting today. I have a large rotisserie of cats I want to be able to play — I think hard about that.

Well, I think that’s all the questions we have for you, Chuck, so thank you very much. Thank you so much for taking the time to do an interview with a more independent magazine.

I’m really into you guys in more ways than one, you know — I still got my Verbicide Magazines laying around [issue #15, Winter 2006].

Go check out the sites hiphopgods.com and beyond.fm to hear [whole album streams], and also you can go check out the archives of the radio show.

Verbicide Free Download: Click here to download Verbicide Select Mixtape 5 featuring “Tear Down That Wall” by Mistachuck (a.k.a. Chuck D)