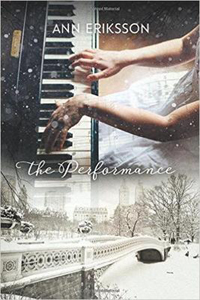

Thetis Island (British Columbia) author Ann Eriksson always delivers a social message within the worlds of her novels. The Performance, Eriksson’s fifth, is no exception.

Related Posts

It is a compelling story set in New York City that features a young, upcoming classical musician named Hana who is studying piano at the Juilliard, and Jacqueline, an older street person who shows up at all her concerts, knitting in the second row. What brings together this unlikely pair is a large part of the mystery of the novel, which novelist Gail Anderson Dargatz has described as “masterful, confident, and lyrical.”

The Performance is eloquent in its description of the strikingly different worlds that coexist with a single city, the wealthy circles of Manhattan’s cultural elite, and the stark existence of those who struggle to survive from day to day.

What prompted you to write your new novel, The Performance?

A crime was committed and I was a direct victim of that crime, but many others were indirectly affected. It was this ripple effect of crime that I wanted to explore.

Does that mean this is an autobiographical novel?

I’m not a concert pianist or homeless and have never lived in Manhattan, so The Performance is not autobiographical in the true sense of the word. However, the emotional essence underlying the story is certainly based on my own reactions to a betrayal at a criminal level. I felt victimized of course, but also embarrassed at having made some bad choices that put me in the position to be victimized, and a lot of shame, which might seem odd as I was a victim not a perpetrator, but I think it can be a common reaction. What had happened to me did not fit in with the way I saw myself: confident, in charge of my life, careful.

The Performance takes place in New York as well as the Canadian West Coast. Why did you choose to locate this novel in New York, and what preliminary work went into developing the setting?

I have to say I thought I was a bit crazy setting The Performance in one of the most iconic cities in the world and where I had never lived. Even more audacious that I was a Canadian. How dare I. But the setting was really dictated by the characters and their story.

I have to say I thought I was a bit crazy setting The Performance in one of the most iconic cities in the world and where I had never lived. Even more audacious that I was a Canadian. How dare I. But the setting was really dictated by the characters and their story.

The place where the lives of Hana and Jacqueline collide had to be such an iconic city, and one with a starkly visible division of wealth and social class. The first time I went to New York, years before The Performance was ever conceived, I was struck by the juxtaposition of extravagant wealth with the most impoverished circumstances one could imagine. So when the novel started to take shape in my mind, the setting was always New York. I spent time in New York twice while doing the research for The Performance. I was very aware that I could never, as an outsider, do the city justice if I tried to write about it from a New Yorker’s point of view, which is why I made both of the main characters Canadian, both seeing the city through the eyes of a newcomer, the way I was seeing it, as a visitor rather than a local.

New York is a big place, so I needed to narrow the setting down to a specific neighborhood. Manhattan, where classical music has such a big presence, with the Juilliard school, Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center all within walking distance of one another, was a natural place for Hana to live. But what about Jacqueline? Would there enough of a homeless presence in such an elite and wealthy area of the city to make their meeting believable?

or my first research trip I arranged a homestay in Manhattan through a home exchange organization I belong to, with a friendly and generous woman whose lovely old apartment is situated in the heart of the Upper West Side, at Broadway and 86th Street, a couple of blocks from Central Park. When she ushered me into her den, where I was to sleep, I was astonished to find a grand piano occupying most of the space there. It was as if I had walked into Hana’s apartment with its creaking radiators, claw foot tub, and the sounds of the Manhattan traffic outside. The next day I began to explore the Upper West Side, expecting that I would have to travel further afield to find enough of a homeless presence; I was surprised to find homeless people everywhere I went, in doorways, on church steps, in Central Park, panhandling on the sidewalk by the Lincoln Center, at the base of opulent skyscrapers. Sad as this reality was for each of those people, I knew I had found the specific setting for the novel, Jacqueline’s “hood.”

Over the course of my two research trips to Manhattan, I attended concerts, interviewed classical pianists, toured the Isaac Stern Auditorium, the Lincoln Center, the Juilliard. I visited homeless shelters, sat on the sidewalk beside street people and talked to them about their lives, interviewed outreach workers and on one memorable night, accompanied a homeless outreach team as they drove through the underbelly of Manhattan looking for rough sleepers. The living conditions I witnessed were profound and disturbing. Every dire situation related in The Performance is based on the real lives of real people living in the Upper West Side.

In the beginning, Hana Knight’s character is unaware of a lot, which makes her discoveries all the more realistic. How hard was it to keep her out of the loop, so to speak? You, of course, knew what was going to happen, but she did not. Was this a challenge?

Hana as a young woman in Manhattan is naïve and unaware, coming from a rather sheltered homeschooled life and fairly insular family, and, of course, absorbed by her music. But the adult Hana, the narrator, knows exactly what has happened, and she strings the story of her naïve past out for Tomas and for the reader from her own perspective, almost as if she is writing the novel she appears in.

I see The Performance as three embedded stories. There is the story that Hana tells Tomas, the story she tells the reader, and then there’s the story she tells herself. Hana is not completely honest in the telling of any of the three. Each involves secrecy, denial, self-justification, and either naivety or downright lies. I wanted the reader to piece together his or her own version of the story of Hana and Jacqueline, including bits from the reader’s own life and experiences, and ultimately, I wanted the reader to start to question or doubt Hana’s story. I wanted to recreate the psychology that follows a breach of trust: the disability to trust again. Was any of Hana’s story true? Was she pulling the wool over her audience’s eyes? And for what end? How reliable is she as a narrator?

Of course, such a structure is a balancing act to pull off. I needed to provide motivation for each of the decisions she makes about what and when she tells who. The process, I imagine, was a bit like writing a mystery or a detective novel, rolling out the clues one by one so the reader thinks she is half a step ahead of the Hana, but still in the dark until the climax.

At an early encounter at Hana’s apartment, Jacqueline refuses to accept Hana’s free tickets to her concerts and insists on finding means to pay for them. I found this added darkness to Jacqueline’s character, indirectly making the reader feel uneasy about her intentions. Before putting those characters in a scene together in which they speak, how did you carve out their separate worlds in the novel?

This novel lived in my head for quite a long time before I wrote anything down on paper. Hana, the young classical pianist, in my mind, stepping outside from a concert hall and seeing a woman, who became Jacqueline, watching her from across the street. A creepy moment. This scene played over and over in my imagination for months. Who were these two women? Why were they where they were, at that time, in that particular city. How would their paths cross? I knew there had to be a mystery. I had to answer those questions for myself and for them.

My conception of character and plot is very much cinematic, both at first and during the writing and editing phase (Maybe I should have been a filmmaker). I seldom find the result completely satisfactory, but that is what drives me forward, that translation of the visual into the literary.

Is there a bit of Hana Knight in all of us? Is there a bit of Jacqueline in all of us?

The simple answer to the question is yes. The more complex answer is that I believe every person is capable of anything, given the right circumstances, from the altruism of a saint, to the most heinous act of evil, even murder. This human capacity makes writing literary fiction endlessly fascinating as it is all about exploring the range of human actions and emotions. Why do we do the things we do? How do we feel about it, about ourselves, before, during, and after? Why are we as individuals or as a society, a species, so capable of self-deception, or cruelty of the greatest degree?

I know I’m never going to be a famous classical pianist like Hana, but I’ve been part of a family, been betrayed by a friend, betrayed a friend, been in love, fallen out of love, even told a few lies (my husband the poet jokes that he tells the truth, I tell the lies). As for Jacqueline, one thing I learned through interviewing street dwellers and reading about the homeless is how fine the line is between being okay and not being okay, having a warm home and having to sleep rough under a tree. For some the line is wider than for others, but a single moment can change a person’s life forever, whether it be the result of an accident, a death, an illness, the choices of another, or as in The Performance, a crime.