Originally published in Verbicide issue #15

Originally published in Verbicide issue #15

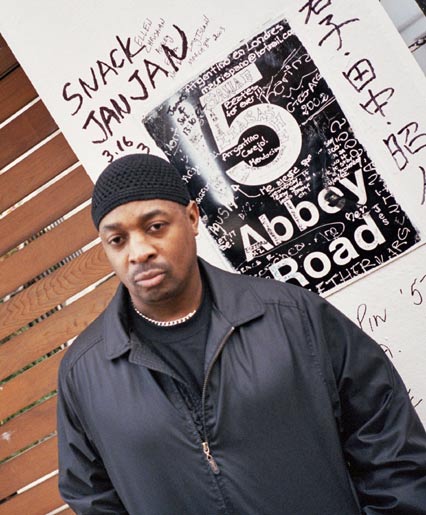

If in 2,000 years hip-hop culture takes on religious aspects, you can be sure Chuck D will have a place among the pantheon of deities, like a futuristic Ganesha with a fitted. Chuck D is an undisputed founding father of hip-hop — he came at the right time, with the right skills and the right state of mind, and history converged around him. If Chuck and Flav had been into Depeche Mode and not Run DMC, the rap game wouldn’t be the same; but as it turns out, they created Public Enemy and made a huge impact in an upstart genre.

Related Posts

Public Enemy injected a social and political slant that was unique and truly revolutionary into a genre that often prided itself on not giving a fuck. Public Enemy’s knack for making caring relevant, hip, dangerous, and funky gave precedence for all those who came after. On the musical front, PE pioneered the layered samples and hard beats that became synonymous with the old school — the repeating dissonant loops became the drone upon which Chuck’s philosophy entered your subconscious. They also introduced white America to the concept of the hype man and made this otherwise dismissive audience wake up and take notice. Public Enemy reminded us that there was nothing more powerful than an idea whose time had come.

But you already know that. You saw the VH1 specials, you know 9-1-1 is a joke, you’ve got an album or two and you get it. What you probably don’t know is what the man has been doing after history moved on, as it eventually must. At 45, Mista Chuck is showing a youth-obsessed culture how to grow and age with self-respect. Between working on a second book, speaking at colleges across the country, touring internationally, running his own label (SlamJamz), handling his myriad of websites and managing to co-host a syndicated show on Air America Radio (On The Real, Sundays at 11 p.m. EST, www.airamericaradio.com), Chuck’s got his hands in more projects than Dick Cheney. And with the release of a new Public Enemy album, New Whirl Odor (yes, Flav’s on it), and a batch of greatest hits releases courtesy of Def Jam, he is not relaxing. I broke bread — or taco shells, as the case may be — with Chuck D as we chatted over the phone about everything from Hurricane Katrina to Little Brother.

(Car noise in the background. At the beginning of the interview, Chuck is going through a drive-thru.)

Hold on just one second, we can get this thing going…Taco Bell. (pause) Hmmm…

You need to get the chalupa.

Well, yeah…I don’t eat meat, so I don’t know what to get here. Anything? (Speaking into the intercom) Yes, what do you have with no meat, the seven-layer burrito? (Intercom voice: Yes, sir!)

How long have you been vegetarian?

No, I’m not vegetarian — I eat fish.

How about that, have you always [eaten] like that?

It’s been about seven years since I ate chicken — and I haven’t eaten red meat since the ‘80s. But when you’re on the road a lot, you still don’t eat right because you’re not making your own food. For instance, I’m at Taco Bell. But you know what, you’ve got to eat something!

You could go to Whole Foods, but that tends to be really expensive.

The where?

Whole Foods, the supermarkets — they usually have those around. You can get good food there but it’s expensive.

The expense, I’m not really bothered by that, but I don’t have enough time. I don’t have time; I’ve got to get down to the University of Illinois.

Related Posts

You’re doing a speaking event there?

I speak at about 40 schools a year — this is the first one this year.

I saw you at Brown a couple years ago.

Okay. That was about four years ago, right?

Yeah, it was great.

So, what’s on your mind?

I wanted to talk about your [new] track, “Hell No, We Ain’t All Right.” I guess that came out basically right at the time when it was becoming pretty obvious that the Bush Administration didn’t care — or just wasn’t prepared — to handle business [in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina].

Exactly.

How has the response been to that track?

Well, I’m not really out there fielding responses. People like it — but I’m not out there trying to gauge it, you know?

How was it talking to Tucker Carlson [conservative MSNBC commentator, host of The Situation] about it, and hearing his take on your track? It seemed like he didn’t even listen to it.

No, but Tucker Carlson does a TV show, so they try to make interesting TV — and you’ve got to understand that going in. He’s not necessarily trying to be on your side, he’s trying to make it interesting, counter-point TV. That’s why he has Rachel Maddow on the show quite a bit. We’re in such nimble-minded times… You can’t blame the public for being “dumb-assified” if the structures that they watch, or listen to, and believe in are just dumb.

I thought it was interesting that callers to the show were basically trying to [use the angle] that you’re a racist for thinking that this [situation was a result of] race, and that it’s your fault to think that the federal government should’ve been responsible for this, to take care of this problem. And then George Bush flipped around and took responsibility for the whole thing, and even [acknowledged] race — that these are poor people and there are racial inequalities. Why do you think he came out and said that?

Because he had to. His back was up against the wall. People saw the pictures, and the pictures didn’t lie. I’m a humanist, and I believe in human beings, and the human situation — that’s why I’m so staunch about racism, you want people to be equal. But that situation was totally disproportionate.

Related Posts

I saw on the show that you brought up some good points about racism and classism coming out now, with the way New Orleans is going to be rebuilt. Do you think that they’re going to try to gentrify New Orleans, kick out all the blacks and make it a strip mall, yuppie area?

Gentrification is rather easy, because all you have to do is throw out a price tag high enough to keep people out who don’t have enough money to stay there. Fifty-four percent of the people in New Orleans rented anyway — which meant the property owners down there are probably of another makeup in the first place. So gentrification is kind of easy…you don’t have to necessarily say it’s racist, but it’s expensive.

I see the same thing happening in Brooklyn, where I live, Crown Heights. Everyday there’s a new building where lots of college-aged kids, like myself, are moving in and taking over. Do you think there’s anything we can do to stop that, or prevent that?

Well, money talks in this country, unfortunately. Unless that situation is subsidized by a bank-loaning system, you’re going to have problems. They have, in some cases, a lottery system where the cost is low enough for everybody to afford, but it’s not about everybody — it’s about whoever is lucky in the lottery.

It seemed like the voice of hip-hop [with regards to] the hurricane was particularly strong — when Laura Bush responded to Kanye West, that blew my mind.

Why did it blow your mind?

Because of the way black music has been treated in this country — and now it seems like it’s a force that has to be contended with by even the first lady. What do you think of all that?

Well, Laura Bush is George Bush, Jr.’s wife. So if you talk about her husband, you expect her to come back and say, “well, that’s stupid.” Somebody talks about one of my kids, or my family, I’m like, you know, “fuck ‘em!” In a weird, twisted way, when George Bush, Sr. came out and he felt pissed off that people were attacking his son, I kind of understood where he was coming from.

Really?

Yeah, of course — they’re talking about his son! (laughter)

That’s true, but he should’ve been schooling his son — I can see what you’re saying, though.

“He should’ve been schooling his son,” yeah, he has schooled his son! (laughter) He probably even knows it’s wrong, but he’s like, “yo, I don’t care.”

I see what you’re saying.

When black people say that shit, it’s like, “oh yeah, but you’re missing the point, you [still have] a responsibility, and blah blah blah…” But there’s human emotion [involved], too. That doesn’t mean that you be irresponsible and you vouch for it, but a person’s got to understand, okay, yeah, you should have that vibe — I don’t necessarily have to agree with it.

But you would expect that the family would come together and support the president.

Mmm-hmm. You’ve got to be ready for that, too. It’s naïve to say, “oh man, he’s the president, he should expect his son to get blasted.” He probably did expect it, but he admitted he didn’t like it, and I thought that was real.

I would like to ask you about the state of hip-hop in contrast with rock, because for people my age — I’m 24 — we’ve accepted hip-hop as just being the dominant form, the “coolest” form, the way things are. When you first started, it almost seemed like hip-hop was this bastard child that nobody wanted to talk about, and rock was the “artistic” form that needed to be copied around the world. Did you notice a time when that started to change, when hip-hop took the reins away from — to say it bluntly — white music?

No. There’s so much racism in the music today. The problem is that the black community and black kids don’t know much of the black history of music — and that’s racist in a way. So, yeah, hip-hop is bigger than ever, but it’s still governed by racist institutions that want to keep control over it! If you ask a black kid, “Who’s Grandmaster Flash?” and they don’t know, obviously there’s a problem. When 2,000 white kids come out to check out Little Brother and there ain’t no black kids there — well, that’s racism because there’s some institutional problem there.

Is it a question of privilege — like, white kids have the privilege to explore beyond what’s presented to them on Hot 97, so therefore they can use the internet, libraries, whatever they have to find out about underground artists?

Well, my belief is that in America, a whole lot of cultural backgrounds aren’t being talked about in households, and they’re not delivering in the school curriculum. And there’s always this curiosity for discovery that takes place for white kids, and curiosity or discovery is warranted and acceptable because it’s part of a learning process. So you can hide things from people, but [when] curiosity starts to figure in, they’re gonna dig for what they’re not presented with, or what they don’t have. And I think that’s what had a lot of white kids checking out Bo Diddley, and Little Richard — previously R&B was played in black people’s homes, and white people were told that their [own] culture was dominant and everything was all good, but they started to look for themselves. So it’s been going on for 50 years now! They would go out and discover. It definitely wouldn’t be presented to you — the underground is not presented. Now, black kids — even in black communities and [throughout] black history — if you’ve had a household that’s been decimated, and you don’t have that type of “passing down” going on in the household, and it’s not in the curriculum — but at the same time, pretty much everybody listens to the one or two radio stations that play black music, and everybody watches that one television station that shows black music — people are kind of used to being told what to do, and told about themselves as opposed to discovering themselves. So whenever you’re told about yourself instead of you defining yourself, then that’s going to lead up to a ball of confusion because you’re going to take whatever’s out there. And that’s why black kids kind of know what’s hot for the minute, but as soon as it’s out of sight, it’s out of mind. And this is why 2,000 white kids will show up for Little Brother — the black kids were never exposed to Little Brother anyway! At the end of the day, it’s whoever controls the radio stations, and it’s not black-owned. In the beginning the black-owned [radio stations] already saw a division between the music. You had fights between Gospel and secular. You had fights between R&B and rap. This allowed the big station conglomerates to find a niche if they were going to have a hip-hop/R&B stations — not really rap, but something that gravitated to a listening audience. I’ll tell you this much — the radio stations that all the black communities listen to, they’re not black stations anymore — they’re corporate-owned…

Clear Channel.

…signals playing black people who sing songs to the black community. You have to call it black music because [for] 98 percent of the music, the people who are doing it are black! So they’re playing black music, but they’re almost, like, “white corporate-owned black signals.” And they have a direct allegiance with major record companies; they have a direct allegiance with the one video company that dominates — and very little of anything else — ownership, demographics — gets in the middle of that mix. But I tell you, if the Clear Channel stations decide to play Jimi Hendrix at four o’clock for about a hundred days, then all of a sudden you’ll have 11-year-old kids humming Jimi Hendrix’s “Foxy Lady.”

That’s true; I’ll tell you from my own experience, I’m Indian, and growing up we didn’t hear anything of ourselves, and when the Punjabi MC track with Jay-Z came out—

Jay-Z, yeah.

— that blew away everybody who I know who are musicians, Indian — we couldn’t believe that was happening.

Exactly. That was one of Jay’s great contributions to music — being able to enjoin the two.

Can you describe the process of writing and recording New Whirl Odor?

New Whirl Odor — it’s another term for “Ball of Confusion” [reference to the 1971 Temptations’ hit], the world is a ball of confusion. Watching the world in [my] many travels over the past few years, and looking at a lot of conspiracy theories and hypocrisies, allowed me to make New Whirl Odor.

There was a line in there that I liked, and I wanted to find out what the inspiration for it was — you said, “liberal friends sometimes pretend/ everything’s changed while nothing’s really changed much.” What’s behind that?

Because black people, the liberals or the conservatives, it’s the same person when it comes down to it, really dealing with the mechanics of what needs to be done. Black people sometimes don’t know the difference between a liberal and a conservative, because they can flip and go on either side at any given time.

The rapper on track 10 [“Revolution”], who is that?

Society — one of [Professor] Griff’s protégés.

That’s a hot track.

You can find him on one of Griff’s albums [1998’s Blood Of The Profit]. Also, on the upcoming Public Enemy New Whirl Odor disc in November, through our distributor, Red Eye, we have an adjoining DVD that is fantastic, too, so you can really enjoy the videos, and full story of everything.

Are you planning to tour with this album?

Well, we’re always touring somewhere. Touring the United States would be good, but we’ve got to fit that in. We usually cover the world — when you cover the world, every other country thinks that you’re not touring! (laughter) When we hit that country, everybody says, “well, where are they?” It’s really funny, man. American culture and celebrity culture are funny because I don’t really consider myself a celebrity or anything of that type, but people are so trained by what they see on TV that they’ll say things like, “Well, are you still doing music?” I mean, what musician stops doing music? I’m an artist, and I was groomed and trained to be a very artistic person.

So, you’ve been talking about [being] international, and I’ve heard you speak before about the multi-cultural and global status of hip-hop. I work with a lot of cats who are trying to represent being Indian, and there’s not much out there for people like that —

— Well, it depends on where they’re looking for it and how they’re going about it. For years I’ve been dealing internationally with cats and I would tell them quite clearly, if they’re trying to make it big in the United States, they’re gonna have issues. If they’re going to try to make it big in New York, they’re gonna have bigger issues. But they could probably be the best that their region can offer — and they have to seriously do it without ulterior motives.

So it’s got to be a grassroots, “start from where you’re at”-type thing.

That’s how everything else starts. Even in this country — once upon a time you had hotbeds like Philadelphia, Miami, the Bay Area — you’ve always had LA — now you’ve got Chicago and Atlanta. And we can’t leave out Detroit with Eminem and Obie Trice and Royce Da 5’9” and all those cats.

I’ve always had in my mind the power and the directness of communication [through music] — there could be a Palestinian MC who, in 16 barres, could basically explain the whole situation right there, and it’s something that kids over here — who don’t really know or don’t really care about the issues — could groove to.

But why would a kid care? A kid has to be able to be made to care. I don’t blame anything on any youth. With the dumbassifying of American culture and the extending of youth culture — you know, you’re 24, but you’re a grown-ass man! In today’s world, you’re looked upon as a kid, but you’re five years, six years into voting! But if you ask somebody what is your status, they’re going to look at you like, “well, you’re a kid, you look so young!” That’s because their asses look so old!

Do you think that’s done on purpose to keep the youth from being a force that could be reckoned with?

There’s no ubiquitous “they.” It’s just the fact that it’s a systematic gathering of trying to keep the pecking order harder to reach, the younger you are.

I was just listening to the last track on the CD [“Superman’s Black In The Building”], and you end the album with an interesting take on the concept of heaven; like you’re saying heaven is something you can have on Earth. Do you think there’s a place for escapist-type music, where people just turn it on and dream about going on a cruise, or to a better place?

Of course. There’s a place for all types of music. There’s even places for the gangster/thug/violent mentality. But the problem is, that can’t be 90 percent of the music because it’s not 90 percent of our reality! And when you judge by the radio stations or television stations or whatever, the projection of it makes it seem like it’s 90 percent of our reality. Cats, you know, they rap and they’ve got 14 naked chicks… (laughter) That’s making a lot of cats mad, number one, because they’re like, “wow, man, they’re getting it like that because they rap.” You’re selling a lot of 12-year-olds a bag of false goods, and when they try to become that and they have the same attitude that they see, then you have a side effect that nobody is around to sweep up and repair.

I guess I took for granted the late-‘80s, early-‘90s when I was learning about music, there were a lot of people rocking the Malcolm X caps and the African medallions, and I know Public Enemy was a big part of that — and it seems that maybe it’s not happening today. With Clear Channel controlling hip-hop in a lot of ways, is there any way some type of empowering movement like that could occur again?

I don’t look at things as always returning or going back; I look at things as manifesting and going forward into some new realm. I will tell you now, there are a lot of young people who felt like the last 10 years they’ve been kept on the outside.

So you think, at some point, that things could progress forward — I guess what I’m asking is, where do you see hip-hop going in seven years?

I don’t know. If hip-hop doesn’t navigate itself, and organize itself, and administer itself, then the genre will have diminishing returns. And “diminishing returns” not just as in people buy it less, but people feel less about it…

It would become less relevant, I guess?

Yeah.