The job was killing me. When I told this to friends they would scoff. What did they know about the misery of grading student compositions? I played in a tennis league with men of various occupations: lawyers, doctors, salesmen, mechanics. They grumbled about high-level stress, long hours on the road, feral bosses. Some had visited my office and seen me with my feet up, the remnants of a cheeseburger-and-fries lunch cluttering the desk, a swimsuit-model site unfurled on my computer screen. Word had gotten around, and my complaints were met with derision.

The job was killing me. When I told this to friends they would scoff. What did they know about the misery of grading student compositions? I played in a tennis league with men of various occupations: lawyers, doctors, salesmen, mechanics. They grumbled about high-level stress, long hours on the road, feral bosses. Some had visited my office and seen me with my feet up, the remnants of a cheeseburger-and-fries lunch cluttering the desk, a swimsuit-model site unfurled on my computer screen. Word had gotten around, and my complaints were met with derision.

Had I been a full professor there would have been no complaints, but in my youth I had drifted out of a PhD program, and now the only gig I could muster was Composition Drudge. Sure, I had a MWF schedule, but I was on campus from seven till dusk and – unlike my elevated colleagues – had no variety in my courses, no teaching of Pynchon or Palahniuk, Splatter Films, postcolonialism, or any of the happy horseshit that eases a professor’s pain after reading the eighteenth essay entitled “My High School Graduation.” A cynical friend in a Midwestern state—himself caught in a similar trap—sent me a T-shirt emblazoned, ALL COMPOSITION ALL THE TIME.

Related Posts

By April I’d had enough, had been driven over the edge by a series of compositions that toyed with my sanity – the worst of the bunch being an essay on Love which contained the following sequence: “Love is an emotion common to all people. Even Hitler had love. He loved his work.”

The University offered me another one-year contract and I signed it because I needed the benefits, but I was determined to find something better. Having excellent communication skills, I had always thought myself a natural for sales, and in the Sunday Want ads there it was, the clarion call that would release me from my bondage: MAKE YOUR FORTUNE IN HOME SECURITY SALES. THE OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME!

I sent my resume to the designated box number and within a week received a phone call from a Mr. Hanlon at Citadel, Inc., who invited me to his home for an interview. It was a house not quite in the country but at the perimeter of town, on top of a hill, in a development of McMansion wannabes. I would have happily lived in any of them. The Hanlon residence was stone and timber, set back from the road, and partly obscured by a magnificent shade tree. A silver BMW was parked in the driveway.

Dan Hanlon, a beefy six-footer, shook my hand at the door and led me down a hall to his office. As we passed the living room, I caught a glimpse of fine furnishings and perfect order: no socks on the floor, no paper-plated sandwich crusts on the coffee table – as in my own digs.

We exchanged pleasantries. He asked me about myself, why I wanted the job, and why I would be good at it. I gave the requisite answers. “All right,” he said, turning his computer screen toward me. “Let’s watch a video.”

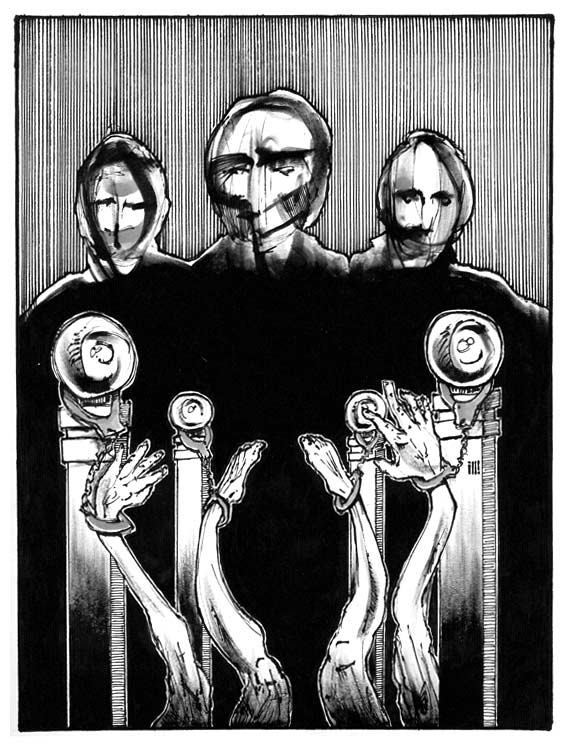

It was horrifying; a montage of documentary footage and dramatizations of crimes against families in their homes, wild-eyed children watching as ethnic types and tattooed skinheads beat, raped, and tortured their parents. The production values were superb; blood and gore ran red as in a Saw marathon. When it was over, Hanlon said, “That’s the reality of America today. And it’s only going to get worse. Most of our prospects don’t need to be sold. They read the papers, watch the news. But if they hesitate, we show them this video and it clinches the deal. Our success rate is one-hundred percent.”

That was hard to believe. It must have showed on my face.

Related Posts

“It’s true,” he said. “When people have the facts, when they really know what’s going on, they can’t sign the contract fast enough.”

“I don’t doubt it, but a hundred percent?”

Hanlon removed a cigar from a box on his desk and offered me one. I shook my head. He lit it, puffed extravagantly, and blew a smoke ring. “Just last week,” he said, “three niggers broke into a home in a Chicago suburb. White family. They beat the dog to a pulp with tire irons. Crippled the parents, made ‘em watch while they took turns raping their nine-year-old daughter. Then they hacked her head off with a butcher knife. Grabbed anything of value they could carry and left the parents lying on the floor with broken spines.”

I winced upon hearing the N-word. Hanlon smiled condescendingly. “You don’t like ‘nigger’? Get used to it. There’s tremendous anger out there. You’ll hear the hate and fear when you talk to homeowners, white and black. Few days ago a black woman looked me straight in the eye and expressed her concern over white-ass cracker Nazis. I agreed with her. She ended up plumping for the whole package.”

For the next thirty minutes he gave me the particulars, the products and services, the generous compensation package. There was something unlikable about Hanlon. He leaned in close and exhaled heavily so you felt his breath on your face. Okay, he was obviously doing well and the job had promise. But his aura was creepy, aggressive and too familiar. I knew I would hate working for him and, after listening politely and shaking his sweaty hand, I said I would think it over even as I was deciding it would be a very fine thing indeed never to be in his presence again.

So I resigned myself to teaching, and entertained thoughts of going back to graduate school. In a few days I’d forgotten all about Dan Hanlon and the Citadel Corporation. It was a terrible shock, then, to open my apartment door one evening and find him sitting on my couch.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

Related Posts

Before he could answer, another man came out of the kitchen with two bottles of Sam Adams. He was short, maybe 5’7”, but his black t-shirt and tight jeans showed off a wiry, muscular frame. There were tattoos all over his veiny arms. With his brush-cut and thick mustache, he looked like a young Gordon Liddy. “Couldn’t find your liquor,” he said, “but I like your taste in beer.”

Naturally, I was afraid. But I had the presence of mind not to show it. Keeping a blank expression, I slipped out of my jacket and opened the hall closet. While putting the jacket on a hanger I scanned the closet for something I might use as a weapon, but the only thing in there besides clothes and shoes was the vacuum cleaner.

Hanlon spoke: “This is my associate, Mr. Salvano.”

“Call me Frank,” said Salvano, settling into an easy chair. He reached across the coffee table and handed a bottle to Hanlon.

I folded my arms and leaned against a man-tall bookcase, trying to appear casual, even to the point of affecting a grin. “I get it. You’re in security and you’re good at what you do. You know how to break into a guy’s apartment.”

Hanlon took a big gulp of beer, and smacked his lips appreciatively. “That’s not why we’re here.”

I nodded. “Actually, I’m glad you dropped in,” I said, dryly. “I was going to call you about the job.”

“Really?” said Hanlon. “Gee, you sure take your time. Fella could get his feelings hurt. Right, Frank?”

“Right, boss.” Salvano held the neck of his bottle between two fingers, the way assholes often do. It was a bad situation. My cell was clipped to my belt. The bathroom was only a few feet down the hall. If I could run in and lock the door, I could call 911 before they’d bust it open. But then I saw movement from the corner of my eye and my stomach jumped. A hulking figure was coming down the hall from the bedroom. He was so big his head almost brushed the ceiling. “Ready when you are, boss,” he said.

I tried to make it to the front door but they were on me. I threw a wild haymaker that caught Hanlon in the throat and he fell over the coffee table. Salvano dove at my legs and I went down, banging my head against the wall. I saw stars, then felt a terrible pain in my shoulder, and everything went black.

When I came to I was lying on my bed, being roughly but efficiently stripped. I couldn’t move, had no strength at all, a sleepy toddler undressed by its parents. My head was foggy, but soon enough I realized I’d been tasered. Hanlon stood at the foot of the bed, rubbing his throat. Salvano busied himself with handcuffing my wrists and ankles to the bedposts. I dimly saw the third member of the crew, a mountainous black man in a green sweat suit. I felt logy until the cold water hit my face.

Hanlon stood over me with an empty glass. “Wake up, boyo. The worst night of your life is about to begin.”

Technically speaking, I was not tortured. Nor was I sexually abused, in conventional terms. There was no prison-style rape, nothing unseemly forced into my mouth. Some slapping and pinching occurred. I felt pain, yes, and considerable terror. Salvano performed exploratory manipulations of my privates that were horribly intimate. They said I would be skinned alive and doused with lighter fluid and set on fire. Sad to say, I babbled and begged for mercy.

And then they stopped. Whistling idly, Salvano unlocked the handcuffs. The black man, Harris they called him, tossed me a blanket to cover my nakedness. I drew my knees to my chest and sat trembling on the bed.

Hanlon explained that the ordeal had not been a punishment, but a training tool. If a prospect declines, a crew comes to his house within a week and does, well…this. Now that I’d experienced it, I would know better how to administer it. “Hundred percent,” said Hanlon. “Soon as the cuffs are off, they sign on the dotted line faster than you can say Jack Robinson.”

“Every new employee goes through this,” said Salvano, trying to sound like a big brother. I couldn’t look him in the eyes.

“That’s right,” said Hanlon. He nodded toward Harris. “Even this big ‘ol booner went down, and it was no easy task, let me tell you.”

Harris threw his head back and laughed, showing gigantic, beautiful white teeth.

They all shook hands with me then. “Welcome to the crew,” said Hanlon. “You start Monday.”

And that, sir or madam, is my story. If you are reading this, it is because you have declined to purchase our services, and ordinarily would be receiving a visit from our crew in a day or so, perhaps even tonight.

Do not panic. Calling 911, for instance, would be futile, as our company is extremely well connected with local law enforcement.

Instead, be thankful that you have been contacted by me—not by Mr. Salvano or Mr. Harris. I am, as you may have inferred, more sensitive than my colleagues, and have devised a creative method for closing the sale without putting everyone through the arduous and humiliating ritual described in the previous paragraphs. You don’t want to experience that, do you?

My card is attached to this letter. Please call me within 24 hours so we can make an appointment for you to sign the contract. Let us meet in my office, where there is ambient music, freshly brewed tea, no threats, and no handcuffs. Just everything nice and safe.

—

Spawned decades ago by the Greatest Generation, Larry Gaffney was for many years a connoisseur of menial jobs, his favorite being captain of a pretzel cart in the streets of Boston. He has also been an English professor, sportswriter, and tennis instructor. One Good Year, his first novel, was published by Level 4 Press in 2007.