Soho Press, 213 pages, paperback, $16.00

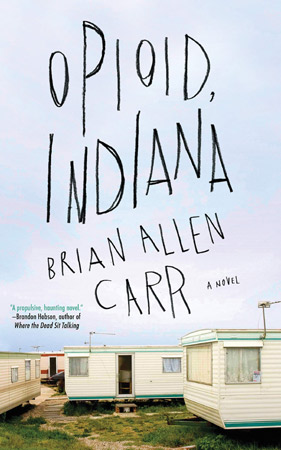

You can’t judge a book by its cover, but I will admit, the cover (and title) of this book intrigued me. Also, while I’d never read any of his work, I have long been aware of Brian Allen Carr, solely because I am familiar with horror subgenre of Bizarro (though I’m neither a big fan nor a detractor of it).

Related Posts

So when I saw this book and realized that the author was the very same behind titles such as The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World and Motherfucking Sharks, published by the short-lived imprint Lazy Fascist Press, I had to check this out — at least in part to see how Carr is able to leap from the world of Bizarro to a more mainstream audience via his new publisher, Soho.

What I found is that like my old friend Jeremy Robert Johnson, Carr is a rare author, capable of deftly skirting the line between the literary and the weird. There are some elements of Bizarro to be found here (e.g., the narrator, 17-year-old Riggle, uses his fingers to make a shadow figure named Remote who tells myths about how the days of the week got their names), but the strange bits neither detract nor distract from what is a straightforward plot of an orphaned teen on a week-long journey to locate his legal guardian, Uncle Joe, who is out on a drug binge. Along the way you see what Riggle sees, and he tells you about his life. It moves along swiftly toward an ending that I should have seen coming but caught me completely by surprise. The story is sad, but not without hope. It is real, it is timely, and it is well-written. It is a book that has heart and deals with its subject matter with sensitivity.

To me, Opioid, Indiana feels like a modern-day Trump-era twist on The Catcher In the Rye. Riggle is suspended for a week from his suburban Indiana high school, much like Holden Caulfield is booted from the ritzy Pencey Prep — only Riggle’s days-long journey takes him through the depressed, drug-riddled streets and cornfields of rural Indiana, rather than through the borough of Manhattan. Instead of sneering at the phoniness of the upper class, he is fascinated by the low-level tragedies he sees in Indiana’s lower class — though, like Holden, Riggle feels an immense disconnect from society. Instead of a NYC penthouse occupied by a sister and parents he can return to, Riggle’s parents are dead, and he has only his addict uncle and his uncle’s girlfriend, Peggy, as family. Holden has Mr. Spencer for a mentor; Riggle is mentored and employed by a brusque but kind restaurateur referred to only as “Chef.”

The comparisons between the novels could go on, but I’ll limit myself to just two more:

First, both Salinger and Carr obviously put a lot of themselves into their respective teenaged narrators (Salinger spent much time in New York, and Carr, like Riggle, is from Texas and now lives in Indiana). In fact, both Holden and Riggle at times feel like surrogates for the authors — vessels through whom they can wax poetic. Given that the two characters were created by the authors when they were well beyond their teenage years, this could be problematic, yet both Holden and Riggle authentically inhabit the world through which they traverse. Carr, though (like me) a teen in the ’90s, writes convincingly from the point of view of a kid two decades his junior — and that, in my opinion, is no small feat.

Second, based on Goodreads reviews, opinions on Opioid, Indiana seem to be nearly as divisive as those regarding Catcher. People either get them, or they don’t. They either love the books, or they dismiss them — Hell, maybe Carr himself would cringe at the correlation.

But again, from what I’ve read, the dislike of these books is often due to the readers’ aversion to the narrators who, though intelligent and observant, are also immature and, at times, unlikable. And the plots are kind of loose; the characters tend to ramble, reporting on what they see and how it makes them feel. If you have little to say, this can be a drag.

But in my opinion, Carr pulls it off well, and I like Riggle. I like what he has to say. I feel empathy for him. As I am reading, I want good things for him, and I am invested in his journey. All that said, I think it’s time I familiarize myself with Carr’s past output.