Jeff Jordan has served as one of the most dedicated modern surrealists for more than 50 years, creating warped and fantastic visions that only connected with the mainstream when he unexpectedly found his musical soulmate, The Mars Volta. Looking for an artistic change after Frances the Mute, Omar Rodríguez-López and Cedric Bixler-Zavala happened upon his advertisement in an issue of Juxtapose magazine and made a call that would end in a Grammy Award for the musical duo and critical acclaim for Jordan, whose artwork for The Bedlam in Goliath was named by Rolling Stone readers as the 2nd best album cover of 2008. It was a three album collaboration that redefined Jordan’s career while giving him two new friends. To this day, he is thankful for the opportunity.

Jeff now splits his time creating gallery art and album covers for bands that found him through his work with The Mars Volta. Gracious, genuine, and brimming with stories, he agreed to reflect on his odd and ever-evolving career.

While surreal, your work often tackles subjects that are now heavily politicized: the environment, greed, violence, and war. As a child of the 1950s and ’60s, do you feel a responsibility to explore these moral and political themes, or is that subtext merely an unintentional product of the way you see the world?

I’ve always been a visual artist. I remember getting my dad to draw trucks for me when I was maybe four years old. My grandfather was a Sunday painter, and he was the guy who I got it from. As I got older, I remained the class artist and it never really went away. I’d copy Frazetta’s women in the Li’l Abner newspaper comic strip, copy comic books — particularly war comics. World War II ended a few years before I was born, and everybody’s dad had been in the war. Atomic bombs and radiation fear led to Godzilla. It was just what was going on at that time.

I came up in the ’60s, and so I was right in the middle of the hippie thing, although I considered myself a beatnik. So there was a lot of stuff going on. Social upheaval!

I’ve done a lot of different types of art. The stuff people know me for has pretty much all happened in the 21st century. Before that I did a lot of other stuff: Cubism, pop art, you name it, I probably tried it at some point, trying to find out who I was. Surrealism always kept coming back. I share my birthday with Dali, but was actually a huge fan of Max Ernst, who really got to that “unconscious” place. Thousands of influences — thanks for not asking who they all are.

I tried my hand at straight-up traditional landscape painting, and probably might’ve been able to make a career of it, but it got boring after awhile. I sold all those paintings, but it got to where I couldn’t even think about that stuff. I was mostly interested in painting what I was thinking about, rather than doing something I was looking at. Before the stuff everybody knows me for, I spent 12 to 15 years studying Picasso and the Cubists. I evolved that direction three or four times. I’d get to a point where I couldn’t do that anymore, and that’s how it goes for me. I was always interested in a lot of stuff, and it actually took many years and a lot of exploration to become me.

To answer your question, I’d say I didn’t actually feel a responsibility to deal with the moral and political themes you mentioned, but I was headed toward social and cultural criticism at a pretty early age, anyway. But I always feel the need to temper criticism through humor, big time. In other words, I had to do all the other stuff that adds the various components to my own “big picture,” the things you do on the way to racking up those 10,000 hours. Keep in mind, I grew up reading cutting-edge science fiction, which is another form of social and cultural criticism, maybe. One thing leads to another, so I’d have to say I was one of those late bloomers — at least in terms of eventually creating the work I became known for. Probably for the best. If I’d become known when I was younger, I probably would’ve had too much fun and destroyed myself.

At any rate, I find that no matter what I do, it eventually gets boring. Part of that is a desire to always improve my skills. I know people who’ve been painting landscape and still life for 30, 40 years, and I can’t see how they do it. Their work doesn’t necessarily change that much in all that time, in my opinion. It’s all about the journey, after all. The destination is the same for everybody. So I keep moving around, artistically speaking. Right now I’m down with surrealism, but that doesn’t mean I’ll always be there.

You depict your animals with a lot of ferocity, majesty, and grace. Where does your reverent eye for animals come from? Do you own animals? What do you feel is the ideal balance between animals, nature, man, and technology — and do you see it becoming realized today?

Maybe I’m more of a social misfit or something. Maybe I’m more of an animal person, rather than a people person. I’m pretty much of a hermit by choice. My sweetheart Nancy and I own an aquatic turtle and a most amazing polydactyl (extra toes — 22 in his case) cat named Nolan — what a guy! I guess the core of it is that animals are who they are. They’re pure from the heart and what you see is what you get. I’ve always had an appreciation for the Native American view of life. The Father Sun and the Mother Earth. Take what you need from the Earth, but use what you take. Leave some for others. In a lot of ways, humans are a curse. America is a huge curse. I read somewhere that for everybody on the planet to live like Americans, we’d need 2 1/2 more planets to have the resources to do that.

Related Posts

Probably the ideal balance between animals, men, nature, and technology was pre-Industrial Revolution, a couple hundred years ago. Now it’s totally screwed up. How many species go extinct every day, now? Humans are responsible for all of it, I’d say. I remember reading the Doctor Dolittle books around age 10 or 11 and I wanted to be him, to be able to talk to all of the animals in their own language. Not like you’d really have to wonder about what might get said. I don’t know about anthropomorphism, but my cat and I really understand each other, just short of actually using language. I saw a bumper sticker not long ago: “The more people I meet, the more I like my cat.” I could really relate to that thought.

In creating surreal imagery, how do you gauge if a painting has skewed too close to reality in terms of your realizations of people and places? Do you ever get the urge to draw from real, recognizable people or events?

If it’s really surreal there’s no way to plan that. If you did, it wouldn’t be surreal. Since 95% of what I do begins as a collage, I tend to decide at that point. I draw and paint from reality a lot. There’s a lot of work that nobody sees. For example, I paint small still life images for my sweetie. Still life is fun because after the painting’s done, you get to eat the model. I just painted three Forelle pears in anticipation of a surreal painting. They’re yellow with all these bright red spots — amazing colors! And they taste really good. It was great; I finished the paintings before the fruit rotted.

Sometimes I like to paint a small landscape. There are landscapes in most of my paintings, anyway, but these days I generally paint a straight-up landscape due to some relevance in our personal life, mine and Nancy’s. She’s from Minnesota, originally. I went back to visit her several times during the long-distance phase of our relationship. I fell in love with some of the old grain elevators in the Midwest, considered using one or two in paintings, and ended up doing paintings that might be considered studies for those paintings, (which haven’t yet materialized, but there’s still time) and they make good Christmas gifts for Nancy. They aren’t for sale, just done because I love her.

I read that during Vietnam you spent time as a radar site security cop in Greenland, where you explored underground comics out of boredom and isolation, eventually honing your craft as a painter. Did you ever have a genuine interest in creating sequential art?

I was 18 in 1966, and Vietnam was heating up. I didn’t want to go to college, didn’t want a student deferment, but I didn’t want to get drafted, because that was a guaranteed ticket to ‘Nam. I joined the Air Force, totally clueless, but I succeeded in my primary mission, which was to stay out of Southeast Asia. I also managed to become serious about becoming a real artist. It didn’t actually happen in Greenland — that place was too weird for anything. I came back to the States, Vandenberg Air Force Base, where I was a missile guard — more Science Fiction in daily life. At that point, I was interested in sequential art.

My childhood ideal was to do a daily newspaper comic strip, or maybe draw comic books. Marvel was on the rise, but I really knew that wasn’t gonna be where I went. I’d been into Rick Griffin when he was doing Murphy the Surfer when I was a teenager. Then the psychedelic thing hit and Griffin was doing what I considered then, and still do now, the best of the psychedelic dance posters. R. Crumb came along and Zap Comix and all the underground stuff got going, and I was really into that. In the ’70s, along came Moebius, Bilal, and all those French guys. Moebius is probably my biggest single influence, absolutely.

When I got out of the Air Force, I was heading toward comics, although when I saw Moebius a few years later I think I started drifting toward painting. It seemed like a lot of what I was thinking would translate better into paintings, and that’s where it went, for sure. But I still love sequential art. Geof Darrow is a current fave; that guy’s nuts! At any rate, in the early ’70s I actually was in contact with Bob Rita at Print Mint, which was an early underground comix publisher. I did the first book — less the front and back covers — and it turned into something that could’ve gone on for a long time; but in doing that one book I realized I’d be bored to death doing sequential art, so I moved on.

Related Posts

That being said, the thing I really took away from the time spent doing sequential art was basic design skills. Like ideally each frame of any page of any comic book should be a standalone kinda thing. Before I did that, I remember taking a life drawing class at the local junior college. I remember the instructor said, “Jeff can draw really well” — I still don’t think so — “but he needs to work on designing his pictures better.” Then I drew that book. Didn’t really know what I was doing at first, didn’t even really have a story.

Oddly enough, when it was finished, I had a story, and for some reason ended up taking another life drawing class from the same instructor. This time it was, “He has a real good sense of design.”

Because of your background in collage, you still draw a lot of inspiration from torn fragments and images on paper. It reminded me of a Norman Rockwell exhibit I recently saw that featured both his paintings and the photos that inspired them. Do your initial collages ever see the light of day?

Norman Rockwell is one of the greatest storytellers of all time. Reviled in the art world as a mere illustrator, he’s finally gotten the recognition he so richly deserves. I love that book of his working photos, just one of several Rockwell books I own. I generally can’t afford to hire models, but sometimes it can be necessary to have some form of reference. Nobody really works from life anymore, I don’t think, so photos are invaluable. I always enjoyed photography, particularly black and white. It influences how I design paintings. Like, I try to make paintings that look as if they’re based on a funky snapshot or postcard.

I did a little bit of collage in high school, and then years later met John Pound, Godfather of the Garbage Pail Kids, and a good friend. At that time, he was doing sci-fi book covers, and he made a lot of robots using collage. He’d cut out parts of cameras, cars, motorcycles, metal stuff, and he’d come up with a robot. That really blew my mind, and eventually, at some point when I was getting tired of whatever it was I was doing then — straight-up landscape, I think — I jumped into collage. The first stuff was just putting things together, no real focus. That stuff is hard to categorize. I was just getting some hours in. Before too long, since I was deeply into my Picasso studies, I started coming up with something between Picasso and Vargas, sort of Cubist pinups.

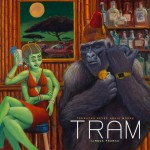

At some point, people started asking why all the paintings were of white women. So, I started doing all races, all ages, all sexes, still strongly influenced by Cubism. The “Dwarf Dancing” painting on the Amputechture disc is an example of that — one of the very best, actually. When that area of exploration got used up, I went into more abstract stuff, and at some point I again got tired of what I’d been doing and moved out of Cubism and back into more Surreal images. I’ve always considered my giant creatures to be a form of fluffy Godzilla-ism. Collage is really interesting — anybody can do it.

I generally consider the collages to be sketches, but it’s hard to really say that. Collage is my most prolific medium, and there are many collages that I consider interesting, but that I also know I won’t end up painting. For one thing, there’s a certain degree of redundancy when I come up with some collages. Like, I keep doing mermaid collages, even though it would be totally boring to me to paint them over and over. But I’m bearing down on 1,700 finished collages, many of them variations on a theme, and lately I find myself being maybe a bit less choosy about what I put in my collage books. Less serious, more one-liners. I put them in those black bound artist sketchbooks and I’m almost through volume 10. But the point would be that there are many collages, and most of them would stand alone.

Last year and part of the year before we endured this seemingly endless remodel of our home — the supposedly four-month remodel job that ended up taking more like 16 months. It really drove me crazy, almost literally. I couldn’t concentrate, but I needed to be there in case decisions were needed. I think I finished two paintings during the construction, both album covers. I totally blew a cover for a band from Brazil, lost that potential market, and went through a personal version of Hell in that it was pretty much impossible for me to paint with any intent. I’m still putting myself back together, actually. But, at the same time, I came out with close to 300 collage images. So it wasn’t a total waste of time.

So there’s a lot of collages. I suppose in my dreams there might be a book of just collages –plenty to choose from. Another idea that seems vaguely interesting would be a different book with the collage on one page, and the painting next to it. I wouldn’t want to do shows of collages or attempt to sell collages as a separate work because I’d hate to cut them out of the books. My little cross to bear, I guess. I have no interest in self-producing books. That sort of thing would best be left to someone whose job that is.

You’ve said that musicians aren’t necessarily visual people, which I thought was a simple but astute observation. Did working with The Mars Volta give you any other pearls of wisdom that you could pass on to other aspiring painters/cover artists?

Omar [Rodriguez-Lopez] and Cedric [Bixler-Zavala] are both very visual people, so I wasn’t saying that about them. But Graham Czach comes to mind in that way. He contacted me to do his Lucid cover, and I came up with the basic image that turned out to be the cover, title of painting “The Widow.” When we started, he was wanting the mermaid to be sitting on the devil’s lap and also a spiral staircase that went to Heaven or Hell, depending on which way you went. I kept trying to tell him I couldn’t make all that work — it was way, way too busy. In the end, I spent close to eight hours drawing out a spiral staircase, just to show him, and he got it. What can I say? It was also his first solo album, and he wanted the most bang for his buck. Graham’s a great guy, and in no way am I bitching him out. Just saying.

Working with the Mars Volta was a life-changing experience in many ways. Before The Mars Volta, I was always asked to come up with images that didn’t really interest me. It’d be like somebody wanting an album cover and saying, “We really like some of the covers Alex Grey did for Tool. Could you do something like that?” Well sure, but why? Give Alex a call, you know? In other words, people only wanted my hands to do something that had nothing to do with me.

When The Mars Volta found me, they wanted me for me. I remember asking Omar what he wanted me to do with the collages they’d chosen to become the Bedlam cover. It was great, and apparently this is something that doesn’t normally happen with Omar — he said, “I don’t want to tell you what to do, that’s your job.” That was one of the great moments in my life! I felt like it was close to something I’d always heard about being in any Miles Davis band: he hired you because of the way you played, not your ability to read music or anything else. In fact, when I did a New Year’s Eve show in San Francisco with The Mars Volta, just before Bedlam was released, Omar and Cedric walked into the space I was showing in right before the sound check, and I had the balls to ask Omar if I could consider myself the visual arm of the band. He said “Absolutely!” Omar and I really understood each other.

So what I took away from those little encounters, and the thing I could share with up-and-coming artists, is this: be yourself. In other words, do what makes you happy as an artist. There are two schools of thought about this. One way is to supply existing markets. Like up here in Northern California, where I live, there’s a huge contingent of landscape painters working plein aire style. Which means they go to some scenic site and stand there and paint what they see. They’re all great painters, but they all paint the same thing over and over and over, which is fine, if that’s what you want to do. The problem is that everybody’s work looks so alike that you need to find a signature to know who did what. Another version of that is dragons, swords, and sorcery, or beautiful women carrying huge weapons, edged or ballistic, in fantasy art. No shortage of boring art. These are all existing markets.

I get bored with dragons, swords, and armed women just as much as straight-up landscape or still life, which led me to my current stance about marketing. I decided to try to create a market only I could supply. I got a lot of shit for it in the beginning, but time has been there for me. As I said before, I’ve done a lot of different things, and I spent a lot of time doing commercial work that left a really bad taste in my mouth and the really lousy feeling of whoredom. My problem is I just don’t really fit into any of the business-driven art modes. Is it a blessing or a curse? I still haven’t managed to decide. What I do know is that I’ve somehow become myself, maybe even the person I was supposed to be.

I had a local show a few years ago, when The Mars Volta was happening for me. At some point a few years before that show, this certain successful businessman I knew came up to me and said, “You oughta paint some landscapes to pay the rent.” I told him if I did that I’d become known as a landscape painter and that wasn’t me. Zoom forward a few years to the show I mentioned. His wife asked me how much for one of the paintings they liked. I told her the price and she said, “Oh, I guess we can’t afford you now.” That little encounter was sweet because they could’ve had my best work for a few hundred dollars back in the day, and they more or less laughed at me. Sometimes it’s great to be the one who laughs last.