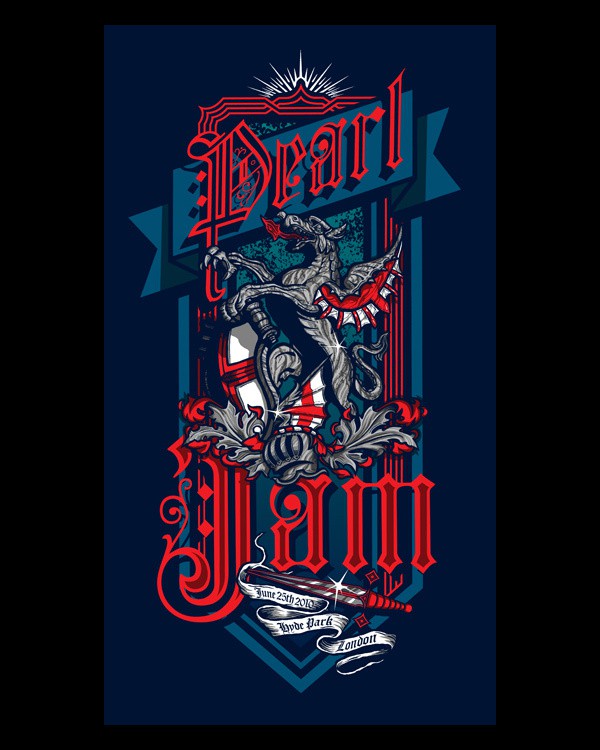

Ever have the dream of writing a letter to one of your favorite musicians and having them write back to you? How about writing them a letter, asking them if they’d like for you to make them posters? And then step it up a notch — ever dream of them getting back in touch and offering you a full time job? Probably not, because it sounds awfully far fetched. And certainly not if you’re talking about a band as big as Pearl Jam. But in 1999, a young Brad Klausen — fresh out of school for graphic design — offered his services as an artist, and they offered him a job.

Since then, Brad Klausen has solidified his reputation as one of the most consistently creative poster designers in the music world. His work (and the thoughts behind it) is chronicled in his new book, From a Basement in Seattle: The Poster Art of Brad Klausen. Klausen was kind enough to take some time to talk about his dream coming true, his evolution as an artist, and what you do after you quit working for one of the biggest bands in the world.

Related Posts

It sounds like an interesting path you took to becoming an artist –did you really have the intention of it becoming a full time job? Or was that more of a hope?

Looking back on it, I don’t think I’d ever intended to be able to make a living doing what I’m doing now. It’s actually surprising to me that I’m able to do that. I’ve always liked art and I’ve always liked to draw. Originally, though, I thought wholeheartedly I’d be a pro hockey player…pretty delusional. Through my teenage years I just figured I’d do this, and then I got a wake-up call that I’d never do this. When I went to school, I studied graphic design because I’d always loved art. I had no intention of a career in it or making money with it. Even when I started working for Pearl Jam, I didn’t make posters for the first five years. When I started making the posters I realized this was a way to make money, and it was more interesting.

So what did you do for the first five years?

I was the in-house designer for [Pearl Jam]. Anything that they needed artwork for, I did: t-shirts, newsletters, mailers, single artwork, album artwork — it grew over time. It started kind of slow, and then they realized that they had this guy in the warehouse they were paying to create art. I was doing all this and then I was making people’s birthday invitations. Jeff Ament’s brother Barry started a company called the Ames Brothers, [and] they were doing all the design work prior to me. They started to make a name for themselves and started charging what a regular design firm would charge for jobs. The band and organization decided they didn’t want to pay that much, so they’d just get someone right out of college. When I first got the job, I was really excited and figured I’d be pretty free to do freelance stuff, but they kept me busy.

Tell me about your new book.

It’s something I’ve been thinking about doing for a while. And it’s missing about 30 pictures — I intended it to be a collection of everything I’ve done, but the publisher said that would be too expensive.

I had talked to a fellow poster artist, Jay Ryan, and asked him how to get a book made. He said you just cold call publishers. I sent out a letter to two publishers, but unbeknownst to me, after I talked to Jay about that, he called his publisher and told them about me. The next day, his publisher got in touch and said, “We wanna do that.” Without Jay’s recommendation, without him being so kind, it wouldn’t have happened.

You reminisce a lot in the short vignettes [that accompany] your art in your new book — does every piece of art you create have a story of its own?

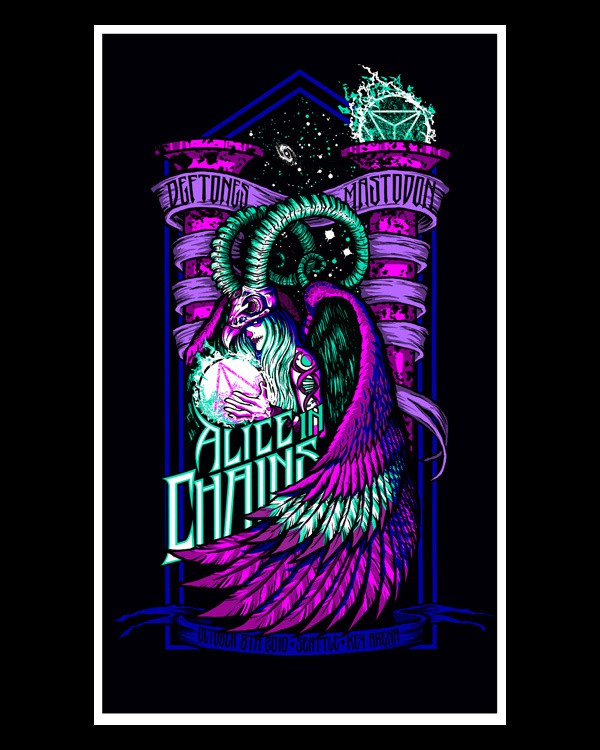

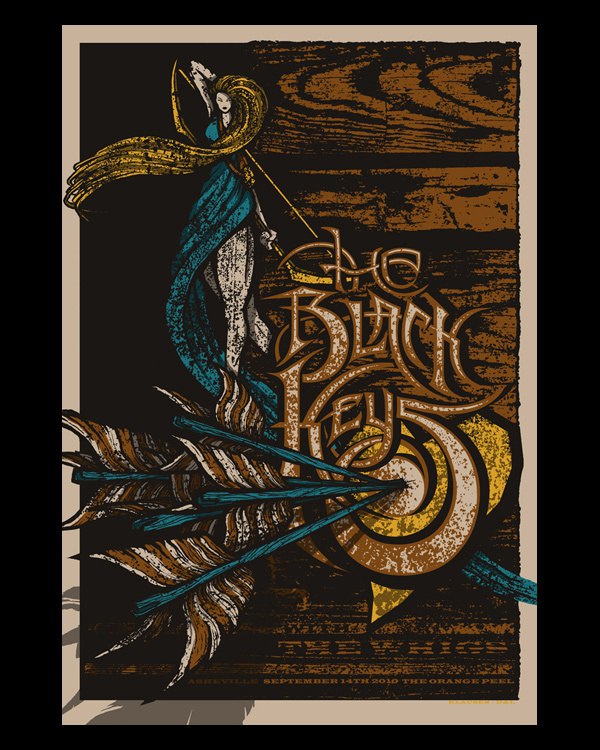

Yeah. When it came time — when I was thinking of putting this book together — I knew that if I looked at every single poster I’ve made, I would remember what I was thinking about. Sometimes the story is not that interesting; I wanted to draw a bird, and that’s the story. Then, most of the time — at least for me — half of the fun of doing this stuff is coming up with the concepts. How is it going to relate to the band, and how am I going to figure this out? Sometimes it’s obvious; you hear a band, and you know this exactly what you’re going to do. And sometimes it’s like, “I don’t know what I’m doing or if this is any good.” [Regarding] each [piece of art] you remember the story totally. Even though it’s five or six years ago, I can see it and remember exactly. It’s like looking at a photo from your past. It’s cool to remember where you were in your head and in your personal life; it’s sort of like a scrapbook.

How long do you spend on each piece?

It varies for each one. Sometimes it’ll take a week, sometimes three weeks. If the concept is strong and I know what I want to do, that’ll cut down time. The other part is just the time consuming part — once you can see an image in your head and it is locked in, can you technically draw it? If you have an image in your head, can you recreate it? That can take some time; you screw up and it doesn’t look right, and you cant get what’s in your head on the paper. Sometimes it’s a struggle and sometimes it’s a breeze. It is dependent on me and where I’m at — if I’m confident in my abilities or stressing out about what I do. On average, [it takes] between a week to three weeks. Three weeks is a long time, though.

If someone asks me to do a job, I’ll say, “Give me at least 10 days.” That’ll give me a good amount of time to get the concept, get it on paper, get it on the computer. In the book, I wanted to have a symbol or asterisk on each piece which was finished at the last minute, but [I] quickly realized that was almost every piece. I’ll be working on a piece for at least a week. It is based on what’s going on in your life at that point.

Judging by what everyone wrote in the book, it’s difficult to tell what your relationship with Pearl Jam is like. [The book hints of] friends who have kind of gotten tired of each other, yet still love each other — is that the case?

Between myself and the band, we still have a very good working relationship. I would say — and I can’t speak for the guys in the band — I think they were surprised when I decided I wanted to quit and leave. I think they’d have been content with me to stay, [but] I was ready to move on and go do other stuff. I was ready to go; I had been wanting to quit for a few years. I quit in the summer of 2008 — it was when the financial stuff was all bubbling to the surface, and I’m quitting a job that most people would die to have. I knew I had to quit and it was time to go, but it was certainly scary. I’m sure my family was thinking, Why are you quitting? You’ve got a good job and health insurance.

Related Posts

Did you consider trying to publish the book with Pearl Jam as backers?

The Ames Brothers put out a book of all their posters. They contacted Pearl Jam and [asked the band] to help them out. Pearl Jam said they would do that, but they didn’t want it to just be Ames Brothers — but who has worked with Pearl Jam? That’s a short list. So they [agreed], and a couple of my posters are in that book as well. When it came time for me to put out my own book, I didn’t want to keep being attached to them — I wanted to do this on my own, and not be beholden to somebody. It would just make the waters a bit more murky — people in there who might be controlling or make decisions. I wanted to have control of the reins. I think they might have gone for it, but I don’t know.

I wouldn’t be doing any of this if it wasn’t for working for Pearl Jam. I’m beyond grateful for that opportunity — the fact that they have a poster collecting cult has helped me tremendously. I’ve always been super honored and grateful; at some point it felt like riding someone else’s coattails, though. At what point am I going to step out on my own without them, knowing full well that the only reason I can step out on my own is because of them? It’s an interesting situation, to work for a band like that that’s had that sort of history and that much success over the globe.

Who have you always wanted to work with?

In this day and age of email it’s unbelievably easy to contact people. [You can] contact the band’s manager or [the band directly] from their webpage. That’s how I got the jobs with Pearl Jam and Queens of the Stone Age. As far as bands I want to work with but haven’t, [there are] two I’d kill to work for — but they both seem to have different approaches to their art: one is Radiohead, and the other is Tool. Thom Yorke has an artist friend from college that they use; anytime you see a Radiohead poster, though, it is done by the promoter, not the band. I’d love to do something for Tool, but their guitar player, Adam Jones, does all theirs, and he just recently got into designing block posters. Those are the two bands that I’m hoping to work for. I’ve kind of stopped holding my breath, though.

Do you have any advice for artists who’d like to do their art full time?

That’s a tough question. I would say…it’s so hard because music is auditory, right? And visual art is visual. If you listen to music, you listen to it, but what does music look like? Everyone sees something different in their head when they hear music. It’d be like crossing any of the senses. If you were to feel something with your hand and have that tactile sensation, well, describe what that tastes like. You just have to really be open-minded, and just sit down and try to figure out what sort of emotion comes into your mind when you hear this stuff, and how you would translate it. How do you draw something to represent sound? That’s a really difficult task. The more you expose yourself to new art and music, the better you get at it. It’s tricky.

As far as getting started in this field, I would say that you have to be unique and have your own style — be somewhat different. I think some of the best artwork for music — and art in general — is strange. It’s something different and something you haven’t seen before. If everyone is going to paint a bowl of fruit in art class, how is yours going to be different than everyone else’s? You are going to have to put yourself in it and make yours stand out.

Also, it’s like the old saying, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice.” You’ve just got to keep getting better.

Related Posts