Vintage Books, 288 pages, paperback, $15.95

Vintage Books, 288 pages, paperback, $15.95

Close to the Knives is possibly the most powerful book I’ve ever read, and if I’d had a highlighter handy to mark all the profound quotes and passages I’d like to reference at a later time I’d have turned a third of the book yellow.

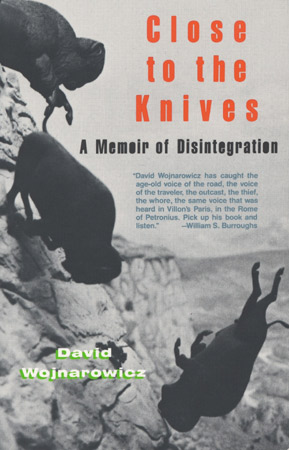

My copy has a pullquote on the cover by William S. Burroughs praising Wojnarowicz, and a few of the more critical reviews on Goodreads suggest that it is “disjointed.” I was wary going in, and the first 23 pages of the book (the first two very short chapters/essays, “Losing the Form in Darkness” and “In the Shadow of the American Dream”) had me worried, as they are indeed disjointed, directionless navel-gazing. I almost gave up, and I’m so glad I didn’t.

We are born into a preinvented existence within a tribal nation of zombies and in that illusion of a one-tribe nation there are real tribes. (p. 37)

Close to the Knives is many things.

It is an important, highly emotional historical document written about the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s by someone who was there, on the ground floor, watching his friends die, and ultimately died himself because of it. He savagely outs those in power — think right-wing politicians and church leaders, primarily male — as the information-suppressing, bigoted, and hugely evil brutes that they were, and continue to be.

Who knows that the vatican and the catholic archdiocese have issued statements that “it is a more terrible thing to use a condom than to contract AIDS.” (p. 160)

During the years of the Reagan administration our president was completely silent about the spread of this epidemic. It took almost eight years just to have a few public posters dealing with AIDS and these posters were only printed in english, as opposed to spanish or any other language. The small AIDS campaign effected by city governments was so unimaginative that it could only state: DON’T ASK FOR AIDS, DON’T GET IT. One doesn’t get AIDS by “Asking for it.” One contracts AIDS through ignorance and the denial of pertinent information that could be used by people to safeguard their sexual activities. (p. 134)

It is a travelogue that takes you across the United States and through the dregs of New York City in a very specific time, far away from now when the average apartment in Manhattan costs about a million and a half dollars.

Related Posts

It is a laser-focused study and critique of our American society. Our false morals, the blind eye we turn to abuses that do not directly affect us, our perverse relationship with media, our glaring hypocrisies.

Dismissal is policy in America. … If there is homelessness in our streets it is the fault of those who have no homes — they chose to live that way. If there is a disease such as AIDS it is somehow the fault of those who contract that disease — they chose to have that disease. If three black men are shot by a white man on a subway train — somehow they chose to be shot by that man. … Most people tend to accept this system of the moral code and thus feel quite safe from any terrible event or problem such as homelessness or AIDS or nonexistent medical care or rampant crime or hunger or unemployment or racism or sexism simply because they go to sleep every night in a house or apartment or dormitory whose clean rooms or smooth walls or regular structures of repeated daily routines provide them with a feeling of safety that never gets intruded up on by the events outside. (p. 150-151)

It is a study of mortality; practically a staring contest with death itself, looking it in the eye and discussing it frankly and directly. In such an emotional set of essays, Wojnarowicz’s view of death frequently changes — sometimes he seems to wish for death, sometimes he seems to want nothing more than to live, if not out of love of life but for feeling that he has much left to accomplish on Earth — but he deals with it head on, which is more than you can say about many people.

Americans can’t deal with death unless they own it. If they own it, they will celebrate it, like in the air force base museum of the atomic bomb, where whole families of camera-toting tourists gather after the required i.d. security checks. In the gray-carpeted rooms, they walk the mazes of portable screens and platforms and enlarged photographs of death and incineration as seen from a discreet distance. The distance is far enough so you can’t see the bodies, only the architecture. (p. 35)

It is a personal history. It is a character study of the people in his life, presented as they are, or were. Wojnarowicz can be sentimental and affectionate, but never sugarcoats the faults and activities of his peers.

It is the study of a seedy underworld I’ll never be a part of, yet it is also an homage to the preciousness and brevity of every life, and a celebration of the fact that we are here for just a little while — and that so many of us don’t acknowledge that temporariness until we are staring death in the face. He explains what it is like to watch your friends die, one by one; examines how they deal with their lives coming to horrific ends, one after the other.

We all turned to the bed and his body was completely still; and then there was a very strong and slow intake of breath and then stillness and then one more intake of breath and he was gone. … I tried to say something to him staring into that enormous eye. If in death the body’s energy disperses and merges with everything around us, can it immediately know my thoughts? But I try and speak anyway and try and say something in case he’s afraid or confused by his own death and maybe needs some reassurance or tool to pick up, but nothing comes from my mouth. This is the most important event of my life and my mouth can’t form words and maybe I’m the one who needs words, maybe I’m the one who needs reassurance and all I can do is raise my hands from my sides in helplessness and say, “All I want is some sort of grace.” And then the water comes from my eyes. (p. 102-103)

Related Posts

It is one man’s story of what it is like to be gay, to endure things that people who are not likely cannot imagine; and though he is one person telling his story, much of what he says is undoubtedly experienced by many others.

I remember when I was eight-and-a-half … For months I searched the public library for information on my “condition” and found only sections of novels or manuals that described me as either a speedfreak sitting on a child’s swing in a playground at dusk inventing new words for faggot…or that people like me spoke with lisps and put bottles up their asses and wore dresses and had limp wrists and every novel I read that had references to queers described them as people who killed or destroyed themselves for no other reason than their realization of how terrible they were for desiring men and I felt I had no choice but to grow up and assume these shapes and characteristics. .. And in every playground, invariably, there’s a kid who screamed FAGGOT! in frustration at some other kid and the sound of it resonated in my shoes, that instant solitude, that breathing glass wall no one else saw. (p. 104-105)

It is a lengthy study of a tragic character — the final 111 pages dedicated solely to his friend Dakota, a gay man and addict who committed suicide, whose parents destroyed all of his art, writing, manuscripts — everything he left behind that was evidence he ever lived. Even the letters he wrote to Wojnarowicz could not be published due to copyright issues, his parents being the owners of such copyrights.

Suicide is a form of death that contains a period of time before it to which my mind can walk back into and imagine a gesture or word that might tie an invisible rope around that person’s foot to prevent them from floating free of the surface of the earth. … All I see is his absence, a void, a dark smudge in the air where he previously occupied space: “Man, why did you do it? Why didn’t you wait for the possibilities to reveal themselves in this shit country, on this planet? Why didn’t you fucking go swimming in the cold gray ocean instead? Why didn’t you call?” (p. 241)

It is simply too much for me to write about. I just finished the book today, and though it is 276 pages, it feels like the longest book I’ve ever read because it is so dense. So much righteous anger and rage, so much beauty and sadness. So many harsh truths. The book winds down as Wojnarwicz flashes back and forth between stories of the abuse he endured in childhood, the suicide of his friend, and a bullfight he witnesses in Mexico not long after his AIDS diagnosis.

…the bull’s legs jerk out spasmodically, blood issues from its nose and mouth, and it is dead. It excretes a stream of shit from its behind into the pale dust. Smell the flowers while you can. (p. 273)

I can’t really formulate a typical “review,” and I really don’t remember if a book has ever left me feeling so overwhelmed upon completion as this one. I’ve kind of written a lot here, mostly quotes directly from the book, but it feels as if I’ve written nothing. Hopefully enough to convince those who’ve read this review to pick up the book. I’d like to hand out a copy to anyone with a heart, and maybe some to those who don’t who might grow one Grinch-like; I believe it is an essential read.