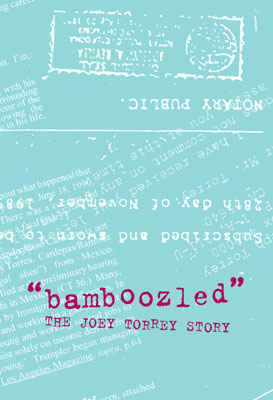

Microcosm Publishing, 128 pages, paperback, $9.95

Microcosm Publishing, 128 pages, paperback, $9.95

Consider, for a moment, some of our greatest nonfiction works — Hell’s Angels, by Hunter S. Thompson, Bill Buford’s Among The Thugs, and Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff — and what they all have in common; indeed, what made them important upon their arrival and makes them the pillars of the form that they are today. Conjoining the three is their ability to avail themselves of a particular section of society — 1% motorcyclists, English soccer hooligans, and test pilots/astronauts, respectively — and, rather than dissecting, cataloging, and mounting them as specimens, depositing one right next to the living, breathing thing, handlebars clinched, pints quaffed, and g’s felt. Now, to be fair, two-thirds of the examples had the benefit of stemming from actual, participatory journalism and first-hand contact with at least some of the events the books detail. The Right Stuff, however, does not, and is instead the vibrating, electric product of reams of meticulous research — vibrant, screaming fruit from a very dull root.

This transportive property — this ability to place us and, in the case of Thompson and Buford’s works, the journalist as well — into the story represents the zenith (and confluence) of nonfiction and art. Literary nonfiction, creative nonfiction, new journalism, gonzo journalism — whatever it is called, the genre hinges upon focusing the muses on animating, rather than conceiving, a story, and it is in this regard that Bamboozled fails.

Related Posts

A svelte 172 pages, Joe Biel’s book deftly traces the savage journey of boxer Joey Torrey, from upper-middle class upbringings to choosing the streets of South Central, from promising amateur pugilist to convicted murderer, drug decrier, and youth activist, and from free man to FBI informant to the pen again. “Traces” is the optimal word here — while relatively exhaustive, there is a distinct lack of verve in Biel’s retelling; the simple black and white of the page is all you ever see reading Bamboozled.

The combination of time, capital (liquid or otherwise), and otherworldly skill needed to bring a coiled baby-snake ball of magnetic tape into fucking literature, as are The Right Stuff, Hell’s Angels, or any other numerous works of new journalism, is exceedingly rare, and one can hardly dock Biel for lacking in any (my educated guess is predominantly the first two); the conflict arises from simply wishing for more. Everything is here, every imaginable seedy mainspring, a fountain of bathos and pathos, sybaritism and solipsism, vice and violence and sport and sex, and Biel draws up the cup and offers up a cold, clear sip.

That we are given water rather than mire is not a bad thing, per se, but merely a tremendous letdown (a tremendous letdown for the reviewer, at least, which may say more about said reviewer than it does about Biel’s book). As an as-factual-as-possible retelling of Torrey’s Homeric arc through the filth and fire, it is supple and laconic; as a compelling narrative, it is a disappointment.

Given how fantastic Torrey’s story is, that of felonious boxer receiving freedom, it is of note that the most intriguing aspects of Biel’s book are the ones which do not directly fall along as plot points. Before meeting with Top Rank boss Bob Arum in a meeting pivotal to the story and to the FBI’s Operation Matchbook, we learn that Joey “walked up behind Angie [Top Rank’s secretary], kissed the top of her head while she was on the phone, and put a basket in front of her.” These tiny details pepper Bamboozled; one can only imagine what could have been had they saturated it.

Also of particular interest are the questions Biel breaks away from the story to ask. A brief rumination on Torrey’s motivations for saving a CDOC guard from a violent assault sparks larger questions Bamboozled could address: “Morality is the sense that you would save a woman being attacked by a mental unstable man because it’s the ‘correct’ thing to do, but what if your brain worked in ways to identify saving a life as the action that was the ‘correct’ way to get out of prison?”

Whether anything can truly be altruistic is certainly up for debate, and Torrey’s widely fluctuating life — felon to youth activist, drug user and condemner, lover of boxing and contributor to its decline — serves as a fine example of the grays that paint charity. Did founding Boxers Against Drugs and working with Youth Development, Inc. in New Mexico come out of a desire to genuinely assist others, to keep them from the fate that had befallen him? Was it all a shrewdly orchestrated con to drum up sympathy and engender glowing statements of character? Was it both? Does it matter? Some would cry that of course it matters, that intentions are, if not everything, at least certainly something; others that so long as someone’s life was improved, nothing else is important, that the results are the final mark on the ledger. It is a question of near unmeasurable depth, one which frames Bamboozled in a different light.

As intriguing as the above considerations are, they cut to the heart of Bamboozled‘s problem, i.e., that the external aspects of the book are the most compelling. Having outside interests is by no means an indictment, nor indicative of a poor book. But given the subject and Biel’s familiarity with said subject, the milieu around Bamboozled, by virtue of being omitted from it, dooms it. Boxers’ necks should be too strong for such an albatross.

—

B. David Zarley is a freelance writer based in Chicago. You can find him on Twitter @BDavidZarley.