Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

I ran into this kid, Fly, who I hadn’t seen in ages. He wasn’t a kid anymore, either. He’d gained about a buck ten to make his weight out at about two flat, and he was now working for the cable company. I did interior carpentry and some unlicensed electric work. Man, did he look bloated; I almost didn’t recognize him as the scrawny punk I used to fuck around with all the time. We clinked glasses to that, asked each other how things was. Not bad, not bad. I told him I’d just gone through a divorce. It was for the best but I missed my little girl. Fly said he was divorced, too, and he missed his wife. He had a little girl, too, a little older than mine, but not by his wife, which is what had precipitated the divorce.

Related Posts

“A keep-a-nigga baby,” groused Fly. “Hell if I’m payin’ child support to that bitch.”

It was weird, I hadn’t thought about Fly for years, even though we’d been inseparable all through junior high and high school, where even the stoners thought we were fuckups for always trying to get high on Glade or toothpaste or whatever we heard would work. Fly especially dug the Nyquil and Mini Thins; I was partial to the Dust Off. And, of course, we’d both gobble down any prescription pills we could get our hands on, even if they were just antibiotics. We’d play up the whole act to the stoners, and would get free drugs sometimes for volunteering to be the guinea pigs.

I tried to think of something to talk about, but couldn’t. Man, Fly must have been tanked. He smelled like shit — literally like shit. You were almost thankful for all the booze covering up whatever that smell was.

“Well,” I said, “see you round.”

“Yeah, you too,” said Fly. I was almost fully turned around, when Fly added, “Remember the runner.”

—

I did remember the runner. It was just after spring break of our senior year at Tom Payne High School, so it must have been near the end; though when you’re in high school you’re too young to have any sense of chronology.

Related Posts

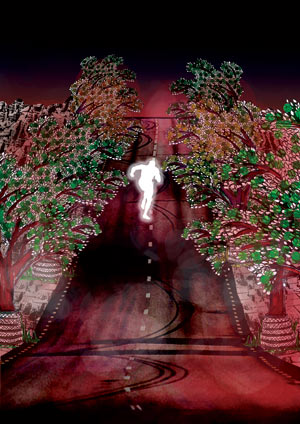

It was a cold Massachusetts night, verging on the next morning perhaps. Spring always came to these parts later than what the calendar claimed, and a fine mist rose from the pavement, enshrouding the figure in a penumbra under the streetlights, as the phantasmagoric runner crested the hill up ahead. On the elms along the avenue, the branches writhed though there was no wind. The figure was ghostly, running like a madman; we could do nothing but stare.

The runner must have been about half a mile off, a glimmering figure in the distance. But even from far away, I could tell that the runner was running as fast as he could. I could observe his utter Zen determination — nothing but his legs hitting the pavement over and over and over and over, as fast as his mind could make them go.

Fly and I had only ourselves recently emerged into civilization after a lengthy stroll in the bird sanctuary, which was big swath of forest that Fly always liked to go to when he was fucked up. It was chill, though there didn’t seem to be any more or less birds there than anywhere else. Fly was a pretty rare bird himself; I think it was Cliff Meacham who came up with the nickname Fly, because he never really said nothing, just sat there like a fly on the wall. They called me Nuggs to make fun of me, because in eighth grade I’d always brag that I could get fresh nuggs of hella-kind Cali bud from my cousin in Humboldt County. I was just trying to be cool, but it wasn’t long before my ruse was found out. So yeah, we were outcasts even among the outcast, you could say.

Which, by some coincidence, was what Fly had been explaining all night to me in the bird sanctuary. (If you just kinda shut up for a while, and waited, Fly would start talking about all this crazy metaphysical shit.) Fly was half Indian, so he knew a bunch of crazy stuff that the paleface didn’t know, about how the Mayans had invented the number zero, and a deadlier astronomy than Copernicus.

“That’s why they put Artaud in the asylum,” Fly explained. “Same with Nietzsche. They’d seen it in Mexico. Baudelaire knew. So did Dali. Jim Morrison was about to figure it out, but the syndicate offed him. They were freaks even to the other freaks. See, it all comes down to the twelve. Twelve’s the worst number there is. It’s what they used to control you with: twelve hours in a day, twelve months in a year, twelve disciples, twelve races of man, twelve eggs in a dozen.”

“I thought there were just four races,” I said. “Black, White, Chinese, and Indian.”

“Nah, man,” answered Fly, “you got three Black races, two White races …”

Related Posts

“There’s not two White races,” I argued.

“Sure there is,” snickered Fly, “there’s the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Aryan master race, and then there’s the rest of you dirty brutes, ha ha.”

“That’s not two different races,” I told him.

“It just doesn’t seem that way,” explained Fly, “because the Vikings did so much raping and pillaging that all you lowland troglodytes have a little bit of Aryan blood in you somewhere. That’s why the French are so arrogant; because they got raped the most.”

“That still doesn’t make twelve,” I pointed out.

“I wasn’t finished,” said Fly. “You also have two Asian races, two Native American races — North and South. Those South American Indians are weird, evil-looking motherfuckers. That’s because they’re the Last Race, the true Lost Tribe, worshipers of the snake that breaks the egg and destroys the order. (That’s what Jim Morrison was onto with the snake, see?) And they have predicted that the Order will come to an end with the twelfth month of the twelfth year of the new millennium at the Winter Solstice, which is their Summer Solstice: the Eschaton.”

“What’s the Eschaton?” I asked with a smirk. We had found out about the Eschaton while looking through one of my mom’s old hippie books for sex scenes when we were in the seventh grade. The book was about a thousand pages long and there were a good amount of sex scenes, but now Fly liked to think that he had made up the Eschaton and it meant whatever he wanted it to mean.

“You see,” explained Fly, either ignoring or forgetting that I knew the truth, “your people’s poison is that Time has a Beginning and an Ending, that it starts with the Seven Days of Creation, and ends with The Second Coming. But Time is like the Corn. It bears its fruit, passes away, and returns for another season. Everyone knows this except for the paleface. That is why the paleface has been so keen to enslave the world; they are afraid of the cycle of time. They want to escape their retribution by praying to their image of Jesus which is actually Caesar, the god of money on the coin.”

It always amused me when Fly got into his “paleface” routine, considering that he lived with his mother who was white and hadn’t seen his father in years. Still, he was right that it seemed pretty stupid for Time to just start up, go for a while and then stop. Why even bother?

“But listen,” continued Fly, “what few know is that there are other ways. Ways through this era and into others. For just like the corn and the squash and the potato, Time can propagate sideways — by tuber, shoot, and runner, in addition to the cycle of Seed and Season.”

Sometimes all Fly’s mysticology just kinda bugged and confused me, and I wondered if he knew what he was talking about with all these philosophers and poets, when he admitted once that the only book he’d ever read was The Ruby Yacht of Omar Khayyam or something, about a man who finds God by being drunk all the time. But tonight it all made sense, for our clarity on these matters had been enhanced from beyond its ordinarily keen ken to a level of superhuman perception, via the ingestion of psilocybin-containing mushrooms, which I’d been given by one of the bussers at the place where I washed dishes. He was a hippie dude named Indra who’d already used them to make ‘shroom tea with his buddy Hasani, a freaky cat I’d met once or twice. Indra was chill, but Hasani had this creepy habit of waiting about half a second too long before he said anything, and then saying it a little too intensely, even if it was just, “hey, maan.”

I brought the slimy dregs from the tea to school the next day, and on lunch break we walked over to Fly’s house and ate the ‘shrooms in some of his mom’s leftover tuna casserole with a Nyquil aperitif (which Fly had heard from “some dude’s sister” would increase the power of the ‘shrooms by inhibiting the brain’s ability to clear the vaunted psilocybin from its passageways). The casserole wasn’t bad, and Fly claimed that the ‘shrooms actually improved the taste of his mom’s cooking.

The dregs apparently still had a good amount of psilocybin remaining in them, because by the time we got to Mrs. Farmer’s sixth period English class we were both starting to feel pretty giggly.

“I hope Mrs. Dirt-Farmer talks about Jesus today,” said Fly with a laugh. Mrs. Farmer was a weird redneck Mormon who was getting a bit feeble in the head, and about half the time would ramble on about God or Pat Buchanan — often even conflating the two — instead of teaching the lesson.

On this day there was no such luck, though I was able to get a laugh from the class when Mrs. Farmer asked if we had any questions and I raised my hand and asked her if she knew where to get any weed.

“That, class,” said Mrs. Farmer, “is why they call it ‘dope.’”

“Yeah, it is pretty ‘dope,’” I snickered to Fly.

After English was over we decided to cut class for the rest of the day, and ended up in the bird sanctuary. The psilocybin had indeed laid my head bare, and I was digging this Eschaton trip that Fly was on. As the sun sank behind the trees, I imagined all that shit going down: the poles would shift, and the song lines would open up, comets would rain down on earth, all that kind of ill shit that Slayer sang about…anarchy would be unleashed, Godzilla and dinosaurs smashing their way through cities, while the cries of pterodactyls filled the skies.

Fly was on his own trip: “This is the twenty-third hour, and the basalt-and-cobalt centipedes who engineer the steam wheels of time from deep within the Center of the Earth must have their due if the final egg is to be broken and the Eschaton imminentized.”

“How come the regular outcasts can’t just turn twelve into eleven?” I asked. “How come it has to be two dozen?”

“It wouldn’t work,” insisted Fly. “They have to be double outcasts. Can you imagine guys like Cliff Meacham and Mark Pale and Nate Barbarowski trying to imminentize the Eschaton? They couldn’t imminentize a clue if they needed one and they do.”

By now it was dark and everything seemed close. We had slipped into silence, following the path of tiny fluorescent lights paid for by the rich, dead Audubon member whose bird sanctuary the birds could apparently give a fuck about. The lights reminded me of Christmas a little. Christmas was stupid now, but I used to like the toys. I remember one time getting a big ol’ Tonka dump truck, and then getting it taken back right away because my little brother wanted to play with it, too, so he tried to grab it and I hit him on the head with it, ha ha.

“This is the end of the line,” declared Fly, breaking my reverie.

I thought he was talking about the trail, so I told him that we could get off once it curved up ahead. There were a number of places you could get off.

“No,” said Fly, putting a toothy grin in my face. There really was something of his namesake about him, a buzzing quality to his laugh, “the end of the line.” The way he said it reminded me of that creepy Hasani kid. “Heads are gonna roll!” shouted Fly in a carnival voice, making a bowling motion.

We both cracked up at that. But once it was quiet again, I imagined the real Eschaton, thousands of corpses bled and rolled down pyramids, sacrificed to the hungry harvest gods. The blood and brutality I could stomach; the swarms of flies so thick it looked like smoke I could not. The bird sanctuary seemed to take on a deeper, softer darkness, and I heard the sounds of millions of insects chirping and buzzing everywhere, all waiting for me to die so that they could lay their eggs in me.

“Hey,” I said,” let’s get back to the road. “I wonder what time it is.”

Fly thought on this. “It’s gotta be at least eight,” he answered, “but it can’t be too much later than three or four in the morning.”

We poked our heads out of the bird sanctuary onto a strange desolate part of the road. There was a cornfield on the other side, and apart from that, nothing to speak of but a 7-Eleven and a strip of darkened buildings up ahead. Thank heaven for 7-Eleven! And not just because I was hungry; the road would have really given me the creeps if it hadn’t been for that neon sign of life.

The convenience store proved, as expected, to be a bastion of convenience. I bought a Slim Jim and gaffled a Hostess lemon pie and a thing of banana milk. Fly horked a can of Mountain Berry Glade. He tried for a bottle of Strawberry Hill, but the cooler was locked, which meant it was past one in the morning. We must have walked a lot farther than I’d thought. On our way out we each grabbed a longer butt from the ashtray outside the store, and headed down the road, smoking.

“Man, why’d you get banana milk, you demented tardazoid?” asked Fly, trying to grab it from me. “What’s it made out of, baby monkey barf?”

I explained to him my theory that if strawberry milk was gross except when you were really stoned, then banana milk must be good when you were tripping. “It’s like one of those SAT questions they made us practice,” I said.

“Maybe if the SAT was made by crack babies,” Fly retorted.

“C’mon, let’s sit down and eat. I’m hungry. Did you get anything to eat?” I asked.

“Nah,” answered Fly.

“Why not?”

“It’s sick.”

“So. It’s food.”

“It’s sick food.”

Sometimes there was no arguing sense with Fly.

We sat down on a brick wall across the road from the buildings we had seen, looking at the black reflections in the dead windows of a small and desolate strip mall. There was a closed Radio Shack, a pizza restaurant that may have been closed for the night or closed for good, and two other unmarked stores. I decided that I would eat the Slim Jim first and the pie second — sort of like a mini-dessert for a mini-meal. I was pretty pleased at my cleverness and was going to point it out to Fly, but I figured he’d just make fun of me. And the banana milk, despite the ‘shrooms, remained pretty goddamn foul — I took two sips and surreptitiously set it aside. The Slim Jim and the lemon pie weren’t that great either. Fly was right. Who came up with all this crap? What was it made out of?

Fly pulled out the bottle of Glade from the pocket of his cargo pants.

“Ah, sweet.”

The inhalant really kicked the ‘shrooms back in, and I felt giggly like I did in Mrs. Farmer’s class.

“That’s why they call this dope,” I said, doing my best Mrs. Farmer impression.

Fly chortled. He pulled out a marker and tagged “H. VRYAD” on the wall we were sitting on.

“What’s H. Vryad mean?” I asked.

“If you don’t already know, I can’t explain it to you. Besides, the ‘h’ isn’t capitalized.”

“It’s capitalized there,” I complained

“That’s because the whole thing is all caps, doofus.”

“Shut up,” I said and socked him.

Fly grabbed me and wrestled me off the wall, knocking over the banana milk, which we both fell into, soaking ourselves as we both tried to grapple free.

“Now I smell like fucking bananas, you fucking scumbag,” shouted Fly, picking up the empty plastic bottle and getting ready to pitch it at my head, then stopping in mid-throw as the lights of a car approached and slowed. For a heart-pounding minute I thought the guy in the 7-Eleven had called the cops, but the vehicle — a dark gray sedan — pulled into the lot across the way and sat there with its headlights on.

Ten minutes later, another almost identical car pulled up and a man got out. He got into the first car, and then after a while he and another man got out and talked for a bit, then both returned to their respective cars and drove off.

“Did you see how they were all wearing suits?” I pointed out excitedly. “It was probably the mafia. We probably just watch someone get paid off for a hit or something.”

“They were vampires,” said Fly matter-of-factly.

“What? Oh, shut up.” I got up from the wall and we kept walking.

“You don’t have to wear a cape and have fangs to be a vampire,” explained Fly.

“What makes you say they were vampires?” I asked.

“They didn’t have auras. Everyone’s got some kind of an aura — at least until they die — but these guy didn’t have one. It was like just the opposite — a shadow around them. Did you see how when that one dude crossed in front of the headlights, he didn’t light up. My dad used to tell me about the vampires. He call them la sombra. When he used to come home all drunk and shit — before mom put the hot iron on his face while he was passed out, ha ha — he’d warn me to watch out for la sombra.”

I was just about to tell Fly to quit fucking with me when the runner appeared. He came over a low hill, dressed in white. At first I thought he’d got caught breaking into a car or something and the cops were after him. But as he closed the distance between us, with no one appearing in pursuit, it became clear he was running from no one save maybe his own personal demons. Perhaps the runner was experiencing his own eschaton, mentally pushing himself through the cycle of time, transcending pain and death, wholly enlightened.

When he crested the hillock the runner had been on the opposite side of the road, but as he came into view he’d changed course just slightly so that he was crossing the road at a long diagonal, making a beeline for the two of us. My gaze locked in on him, and I’m sure Fly’s did, too. It seemed as if the three of us were the only people in the world…the only things in the world, floating in blankest space, as the runner rapidly closed the distance between us. For a second I had an image of an awful banging clangor, and a face he remembered from…

But now the only face that he saw was the runner’s, looking into his clear blue eyes, the insane focus written there, as the runner crossed the center stripe. He was coming right at us, unwavering, like a human train. His veins and tendons bulged, but his face was not flushed and his breathing was not labored. As he took the final strides, I cringed, preparing to be barreled over.

The moment before impact, the runner vanished and was gone.

—

We never did agree on what had happened. I thought it was a collective hallucination or maybe even a real runner. Fly insisted it was a ghost. But you could never tell with Fly whether he was just fucking with you or not. Funny, we were having the same argument years later, I thought, as the booze washed over me and my mind sank into my warm pillow. Or no, I was just remembering…I thought about Fly, and wondered why we hadn’t stayed in touch after graduation. We were supposed to walk together, but I ended up walking with Collin Roberts, who we used to call Collin Cancer, ha ha. I wonder why I didn’t walk with Fly. He must’ve failed, the dumbass.

—

Next morning I was late to work, which was okay seeing as how I was more or less my own boss. The whole day was off kilter somehow. I’d overslept because I’d been having these really intense realistic dreams that I couldn’t remember at all when I woke up. All I knew is that my apartment felt unfamiliar and dingy, and my pickup seemed beat. The whole trip to the jobsite felt like I was taking the back roads, even though it was the same route I always drove.

When I got to the site, my assistant, Cool Dave, was in his beat-ass Cutlass waiting for me, listening to The Dark Side of the Moon. For Cool Dave, the Pink Floyd laser light show represented the pinnacle of the human experience. This fact — and his long hair — is what had earned him the nickname “Cool Dave.” Cool Dave had never done drugs of any sort. He didn’t need to. Cool Dave walked the line between semi-retarded and just real dumb like a tight rope. He was a good worker if you told him exactly what to do. And if he was on the lazy side, it was for the best — no need for him to try to do something on his own and fuck it up. Mostly I used him for holding up big sheets of drywall and bringing me crap. Plus, it was good to have someone to talk to. I paid him a couple hundred bucks or so every few weeks, and he thought it was a lot of money. He lived in the garage of his mother’s house and spent all his time and money on making his own personal Pink Floyd laser light show. I’d seen it once or twice. He’d actually managed to pick up a lot of carpentry and wiring skill, and it was surprisingly well built. The design, on the other hand, was essentially non-existent, just a big mess of lights that was more like a bad traffic nightmare than a laser light show.

Today, though, even the generally oblivious Cool Dave could tell something was wrong.

“What’s eating you, boss?” he asked when we stopped for lunch.

“I ran into an old friend last night,” I said lamely, feeling like I was lying.

“Girl?” asked Cool Dave.

“Huh…nah.” Somehow I couldn’t remember it right, like whenever I thought about seeing Fly last night I thought about the runner instead, or like it had happened back in high school. Had we talked about the runner last night? I felt like maybe I had a mild case of amnesia. I felt my head for sore spots to see if maybe I took a fall and didn’t remember it; nothing hurt, though, so I figured the best thing for it was to get some beers and a steak, see if there was a game on, and pass out with a full stomach at around nine. I told Cool Dave he could have the rest of the day off.

“Aw thanks, boss. You’re the greatest,” and off he drove bumping “Money” in his beater of a Cutlass. I think that guy only had one tape. He probably had never heard anything off any of their other albums except maybe a few tracks off The Wall.

I flipped aimlessly through the radio stations and almost immediately came upon the creepy beginning of “Time,” I think it’s called. A shudder came over me, and then suddenly I started laughing, as tears rolled down my cheeks. Man, that Fly — here he was creeping me out, how many years down the road? That kid was fucking dynamite. He didn’t have to say much to be a trip. I suddenly had a vivid image of Fly tapping me on the shoulder, and when I turned around, he fish-hooked his mouth with his thumbs while holding his eyes way open with his fingers so he looked like some living skull. I think we were tripping on ‘shrooms, because I freaked the fuck out and just booked it.

That must’ve been the night we saw the runner, because that was the only time we’d done ‘shrooms together. But I couldn’t place it chronologically. Was it at the very end of the trip? That seemed kind of right, but…or maybe the skull-face was something that happened in the dream I had, or…

Was Fly in the dream? It would make sense, considering…

Considering that the gate on the barbed wire fence around the abandoned muffler shop was open. I’d lived in the neighborhood for eight year and never seen anyone there. Now there were two parked cars. The models were ten years old, but they looked brand new. They hadn’t aged at all since Fly and I had seen them years ago. It was la sombra. The man who had first gotten out of the car that night long ago stood by the hood of his vehicle, smoking a brown cigarette. I could feel him watching me.

I stared at him and told myself that it was just my mind playing tricks on me. There was no possible way I could recall what someone I had seen ten years ago had looked like, especially someone in an expensive but essentially generic gray suit. Even the cars were not especially unique. But I knew. I stared at the man, trying to figure out how, what it was that made me so certain.

“No one told you when to run. You’ve missed the starting gun,” sang Roger Waters from the radio.

The muffler shop passed behind me and I turned my attention back to the road ahead. I had run a red light, and was bearing down on a runner who had cut across the street, assuming I would stop. I slammed on the brakes as the man careened off the hood of my truck and smashed face-first into my windshield. It was a face I knew all too well, grinning flattened like a child making faces against a glass door. Time seemed to slow as shock kicked in, and I could make out the way each of his teeth had broken in a slightly different way, outlined as they were by the blood pouring from his nose. The runner’s wide eyes gazed into mine, as if signaling some strange completion, as my head pitched forward into the steering wheel.

Had I not been locked onto his stare, I might have hit with my forehead, suffering just a slight concussion. But the eyes, the eyes drew my face upwards, and I impacted the wheel with my nose — a direct hit, forcing the cartilage like a knife into my brain. An explosion of pain, and then darkness. There was no more the pain, no more anything. Just a hollow dry buzz, getting fainter and fainter…

—

Christopher Staley is a semi-frequent contributor to Verbicide, and the author of a collection of short fiction called Nuts. He has written three as-of-yet-unpublished novels, and is the publisher of a zine called VeX and its sister website telecult.com. His interests include linguistics, evolution, mathematics, and napping. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.