Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

Originally published in Verbicide issue #24

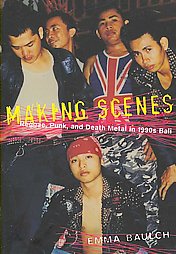

Duke University Press, 226 pages, paperback, $21.95

When we think of independent music in our local city, we think of our art communities pestering one another for promotional spots, mass emails, CDs selling on consignment in small record stores, college radio, beer-funked music halls, silk-screened t-shirts and posters. The world of music seems to have a universal story when it comes to those bands that break on through, or who document their movements. However, there are those movements that, for whatever reason, seem to have been entirely lost on even the most “indie” mental landscape.

Based on her 1996 trip to Bali to research youth culture, Making Scenes is author Emma Baulch’s detailed account on Bali’s independent music scene in the late 1990s. Endlessly detailed, the book’s narrative arch stems from the voices of the bands that were struggling and rising at the time. It also operates like a music genre travel memoir. The book began as a thesis Baulch was developing as a Ph.D student at Monash University in Melbourne in 2000.

“The punk aesthetic,” writes Baulch in the introduction, “was very textured, aggressive.” Culling interviews, concert reports, and local media coverage and reaction to the countercultural movement, Baulch’s writing draws you in without getting too bogged down on the poster font types or the color of the drummer’s nail polish.

Examining the complex identity politics that played out, Making Scenes tracks how various music subcultures — punk, reggae, and death metal — developed in Bali; from open mic nights to MTV Asia, the fascination is multi-pronged, taking readers into the pathologically guarded world of Indonesia’s media.

Baulch is dedicated beyond the after-gig adrenalin kick, and digs deep to reveal how each music scene arrived and grew. “In the early 1990s, death and thrash metal bands were generally unwelcome in tourists bars and hotels, which were reserved for reggae and Top 40 bands,” she writes. According to one member of Bali’s Superman Is Dead, “Underground people should hang out wherever they want; they shouldn’t have to be tied to any kind of genre-based politics.”

The oral history segments never cling to over-analysis, and add textual divergence to this compelling dimensional flashback. Giving voices to the movement in a similar fashion to Legs McNeil’s Please Kill Me, these fascinating asides offer natural glimpses into a world we would otherwise never knew existed. The alchemic reactions that blend and bend culture and political turfs (throw in some media angst) are set against Bali’s youth who are reacting to established forms of alternative music (Green Day, Bad Religion) and begin to mark out their own unique identity through music, fashion, and creating a subculture like no other. Making Scenes dives head first into Bali’s youth’s identity, and it is this passionate that is captured, and fuels the entire book: “The Balinese metal enthusiasts’ role,” writes Baulch, “in broader Balinese identity politics in the late 1990s seems much less clear.”

Quoting Baulch, (who is now a Senior Research Associate in the Creative Industries Faculty at the Queensland University of Technology in Brishbane, Austrialia) is addictive to say the least — the way she puts her thoughts together is remarkable and concise: “Balinese punks localized their genre of choice by devolving from a central hangout to develop roots in a number of home territories scattered across Denpasar…this devolution enabled them to cohere around a countercultural, antigaul (anti-rich kid) alterity, which was spectacularly performed by way of spontaneous interventions in mall space.”

For her intelligence, wit, and passion Baulch is to be commended. Making Scenes is a formidable addition Duke Press’s masterworks of provocative subject matters.