Originally published in Verbicide issue #23

Originally published in Verbicide issue #23

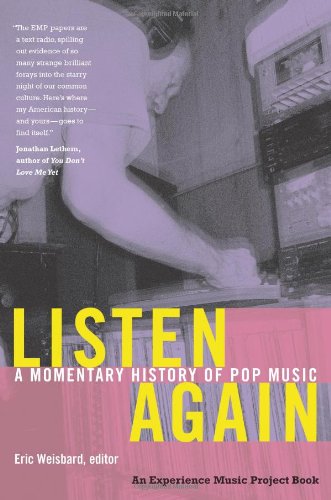

Duke Press, 323 pages, trade paperback, $22.95

Nietzsche once said, without music, life would be a mistake, and without it, Listen Again’s entire mental landscape would not have a single synapse firing, which would be a complete shame. Listen Again is an inspiring collection of music writing on the post-categorical appraisal of how particular songs and artists have influenced our society, long after the sometimes simple melody has faded off our sonic charts, and is, quite simply, a colossal examination of popular music’s growth over the last century. These entry points will fascinate even the casual music fan, while experts of general knowledge and music culture trivia will be intimidated, inspired, and reassigned to these experts. Arguing that pop music turns on moments rather than movements, the book moves in and out of musical regions; the minutia excites and realizes a deeper appreciation of the art form, satisfying fans of every music persuasion.

As the former curator and senior manager of the Experience Music Project from 2001 until 2005, editor Eric Weisberg is certainly qualified to edit such an eclectic musical focus. Listen Again is a salacious time capsule of music moments unearthed. Weisberg’s own entry, “The Buddy Holocaust Story,” is the obscure 1981 story of a college student who billed himself as Buddy Holocaust, a protest singer who protested the protest movements. “The singer knows that he’s being irrational. He enjoys it…A born smartass — with girl troubles, of course.”

The book is not without its share of speculation and subjectivity. In an essay dissecting Poland’s disco pop culture, Daphne Carr declares, “in the romantic vision of the folk as the vehicle of expression for the nation, the idea of disco pop as the next step in the aural tradition is tantamount to suggesting that contemporary Poland is a nationalistic, illiterate, or even nihilistic dystopia.” While Robert Fink’s entry, a fascinating piece entitled, “ORCH5, or the Classical Ghost in the Hip-Hop machine,” is “a story of technology, of machines fetishized, appropriated, mistrusted, misused.” The ORCH5, according to Fink, was one of a series of ORCH samples digitized by David Vorhaus in 1979, “almost certainly sampled from Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird.” The essay traces the sample’s journey into the hands of those who produced popular music connections (Kate Bush used the sample in her 1982 album The Dreaming), and reads like a science article on how a simple music sample infected pop music’s DNA in the early 1980s, and began to grow enormous.

Holly George-Warren’s contribution is a novelistic jaunt through the life of Bobbie Gentry, a former Vegas showgirl who went on to win three Grammy Awards in her first year as a recording artist, and, for a while, knocked the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love” off of the number one spot in the charts. Writes George-Warren, “But Gentry’s impact also foretold the success of a blended pop-blues-country style that would explode in popularity three-plus decades later in artists ranging from Wynona to Shania Twain to Gretchen Wilson.”

Listen Again is a husky buffet of musical and human instances as writers comment on music’s ongoing evolution through social, technological, and political landscapes, which themselves were — and are — continually changing.